Text by Katie Shapiro

Images courtesy of Aspen Historical Society

Early on in Aspen’s 14-year silver boom, before it came to be known in the Victorian era as “Silver Queen City” for its brief moment as the country’s largest producer of the precious metal, it seemed that a different boomtown 11 miles away might have claimed the title. Eager to capitalize on silver deposits newly discovered in the Castle Creek Valley, prospectors from nearby Leadville flocked to the area in 1880 to establish the mining camp later known as Ashcroft.

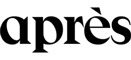

According to accounts by the Aspen Historical Society—a nonprofit that manages both Ashcroft and Independence Ghost Town along with the Wheeler/Stallard Museum, the Holden/Marolt Mining & Ranching Museum, and the largest public archive in the region—the area exploded to a population of about 2,000 by 1883, outpacing Aspen and fueling rapid infrastructure and industry, including two newspapers, a school, sawmills, a small smelter, and 20 saloons.

But Ashcroft’s initially promising silver deposits proved shallow, and plans to build a rail line to the supply town of Crested Butte never came to fruition. Ashcroft went bust by 1885, after a rich strike was discovered near Aspen in 1884. The town’s last resident, Jack Leahy, left in 1935, and Ashcroft has stood abandoned ever since.

The town’s boom-and-bust history has fascinated countless locals and visitors, but none more so than Rob Fedor and Peter Starck, amateur historians who have spent the last decade unraveling a more thorough origin story of Ashcroft. The duo were first enchanted by the magic of Ashcroft and its surrounding mountains in 1975, the same year it was added to the National Register of Historic Places, though they didn’t know each other at the time. (Fedor, then 21 and a new resident of Aspen, and Starck, then 11 and on an annual family ski trip to Snowmass, wouldn’t meet for another 40-odd years.)

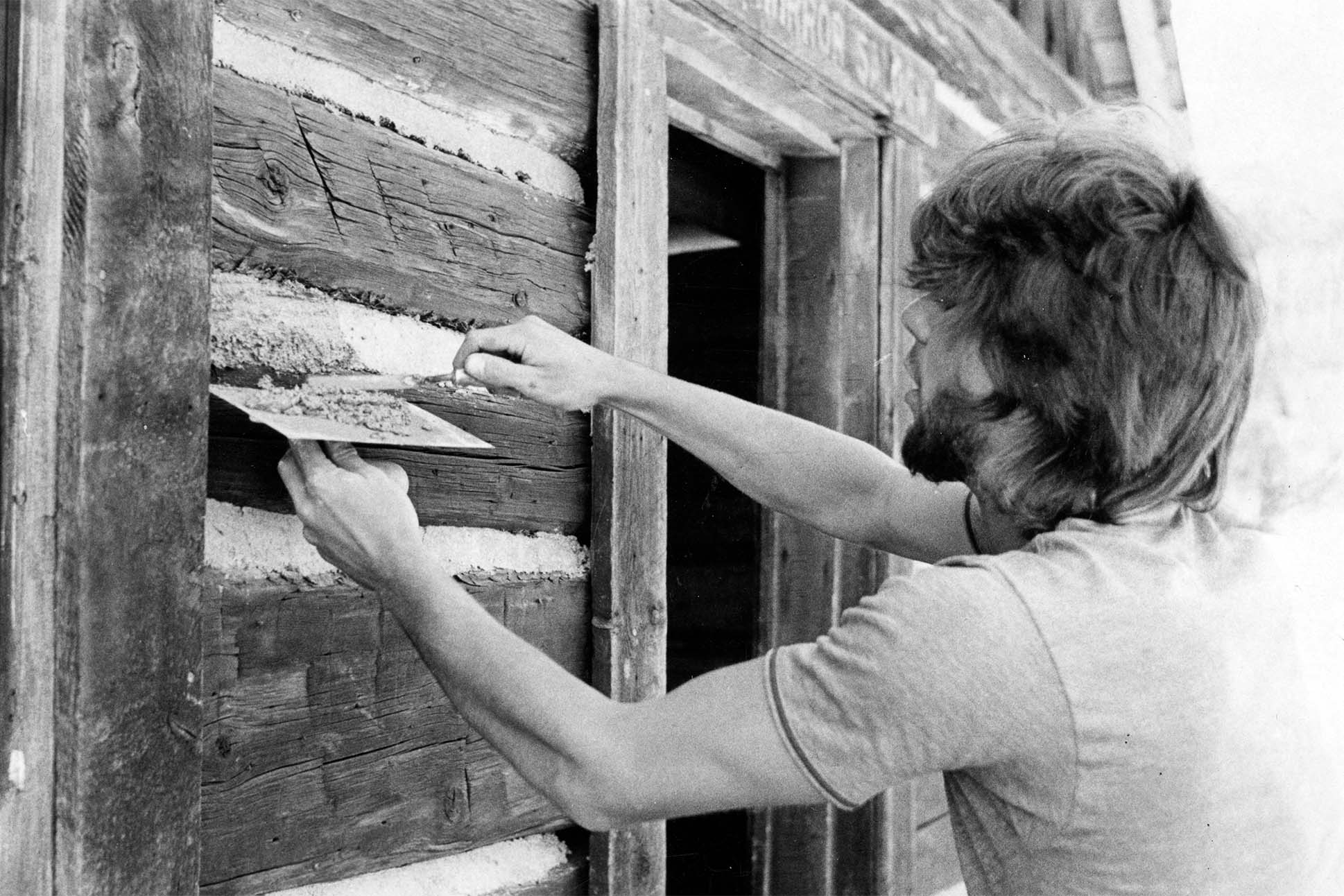

Unmoored after narrowly missing the draft back home in Ohio, Fedor had moved to Aspen and spent a few years working odd jobs around town, earning his keep as a photographer, construction framer, and silkscreen printer, among other vocations, before leaving to find work in other parts of the country. But Fedor never forgot Ashcroft. He’s now based in Florida, where his retirement project is building a replica model of both the exterior and interior of some 30 buildings that lined Castle Avenue during Ashcroft’s prime.

“My years living in Aspen were just enough to lock my heart up,” Fedor says, though he hasn’t returned to Ashcroft since he left the valley in the late ’70s. “But in my workshop, I get to walk the streets of Ashcroft every day. It’s like I’m there.”

It was only in 2016 that Fedor came to know of Starck, a construction engineer in Wisconsin whose efforts to piece together lesser-known aspects of Ashcroft’s past landed him in an article in The Aspen Times. Fedor read that Starck had begun doubting the commonly accepted name of a town landmark known as Hotel View. The hotel was Fedor’s starting point for constructing his replica model of the town, so he contacted Starck, and the two became close collaborators.

“We’re always sharing information back and forth and working for one good, common goal, which is trying to honor people who have been overlooked,” Fedor says. “I couldn’t do any of this without Peter.”

It was upon studying old photographs of the hotel that Fedor noticed the building’s bird and birdcage motifs, a clue that led the men to a woman named Nellie Bird. “There is no connection between Nellie Bird and the original naming of the Little Nell claim on Aspen Mountain, but there are two photographs of her from 1887 in the Aspen Historical Society archives standing very close to it, and another showing her arriving in a wagon,” Starck says. “I was able to identify her in two of them, and Rob found her in the third.”

Fedor and Starck eventually determined that Nellie Bird was a dairy rancher who acquired 176 acres of ranchland in the North Star Nature Preserve on Aspen’s east end after moving to the area from Leadville around 1801. “I’ve been able to identify her in photos due to a noticeable lean from a very serious back condition and noticeable ailments with her hands,” Starck says. “She also had an ailing father and ailing son to care for. Still, she persevered, accomplishing nearly everything herself, and with very little, if any, fanfare.”

With an additional interest in the potential riches of Ashcroft, Bird also set up lodging there, later hiring builder Edmund C. Hawkins to construct the prominent boarding house commonly referred to today as Hotel View but known during its years of operation as the Bird House. Yet despite swiftly growing her reputation as the grande dame of the male-dominated mining community as one of a rare breed of single-mother pioneers (her first husband abandoned her after they moved West from Chicago; her second husband, Henry Bird, left her after only a year of marriage), Bird has been largely left off the list of local legends credited with the success of the era, however short lived.

Bird died at her ranch in 1913 and was buried at an unknown location at Aspen Grove Cemetery, a site comprised partly of land from Bird’s ranch. Few know of Bird’s astute foresight and enduring contributions to the area, Starck says, and he believes there are myriad others whose stories are still missing from the history of Ashcroft: “At this point, I still feel as though I have just started to rediscover the true history of my favorite place on Earth.”

“I’m hoping one day that I’ll find a home for the models,” Fedor adds. “I’d like to see them end up in the right place, where they can educate and do some good. There’s so much undone, so much to tell, that I think I’ll probably be working on it until the day I die.”