By Maura Egan

Photography by Trevor Triano

When most people think of the cultural life of Aspen, they think of Hollywood A-listers like Jennifer Lopez and Justin Bieber flying in for a winter ski holiday or the late journalist and resident Hunter S. Thompson and his various gonzo antics around town. But behind all the glitz and glamour, this small mountain resort possesses a cultural gravitas that has lured world leaders, intellectuals, authors, and other rarefied minds since World War II.

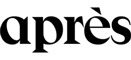

“It’s all because of Walter and Elizabeth Paepcke,” says Lissa Ballinger, executive director of the Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies, which is located on the campus of the Aspen Institute. Walter was a third-generation German intellectual and Chicago-based industrialist. He was a man with heady ideas who socialized with academics and artists, and an aesthete and early champion of the Bauhaus school who welcomed European designers like Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius and artist László Moholy-Nagy when they came to America to escape the rise of Nazism in the 1930s.

Elizabeth was equally cultured and curious, and after she visited Aspen during a skiing expedition, she became smitten with the beauty of the town’s pristine landscape. “This was after all the silver mines had closed and essentially it was just potato farmers, cattle ranchers, and some remaining miners,” says Ballinger. Elizabeth was determined to bring her husband to Aspen because she believed this tiny mountain resort would be the ideal place for the couple to establish a sort of “cultural utopia,” Ballinger says.

They made the trip west in 1945, and Walter came up with a blueprint for the “Aspen Idea.” He envisioned a place where one could nourish “their body, mind, and spirit” through art, music, education, and discussion, as well as physical activities like hiking and skiing. “The idea was to foster all aspects of a more actualized self,” says Ballinger. The Paepckes wanted it to be a place where business leaders, intellectuals, politicians, and artists could come to discuss the issues of the day (think: the World Economic Forum in Davos but with more idealistic goals).

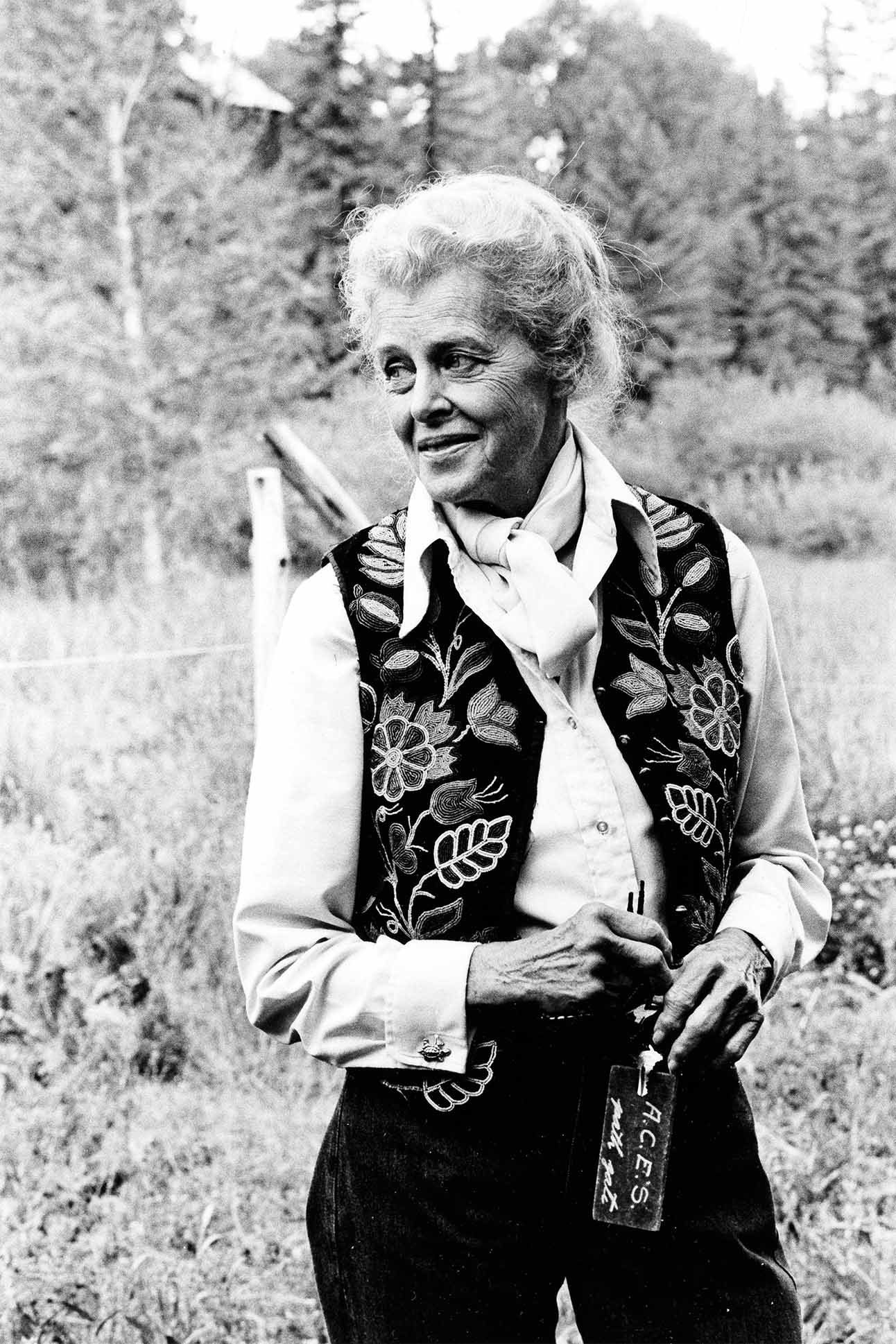

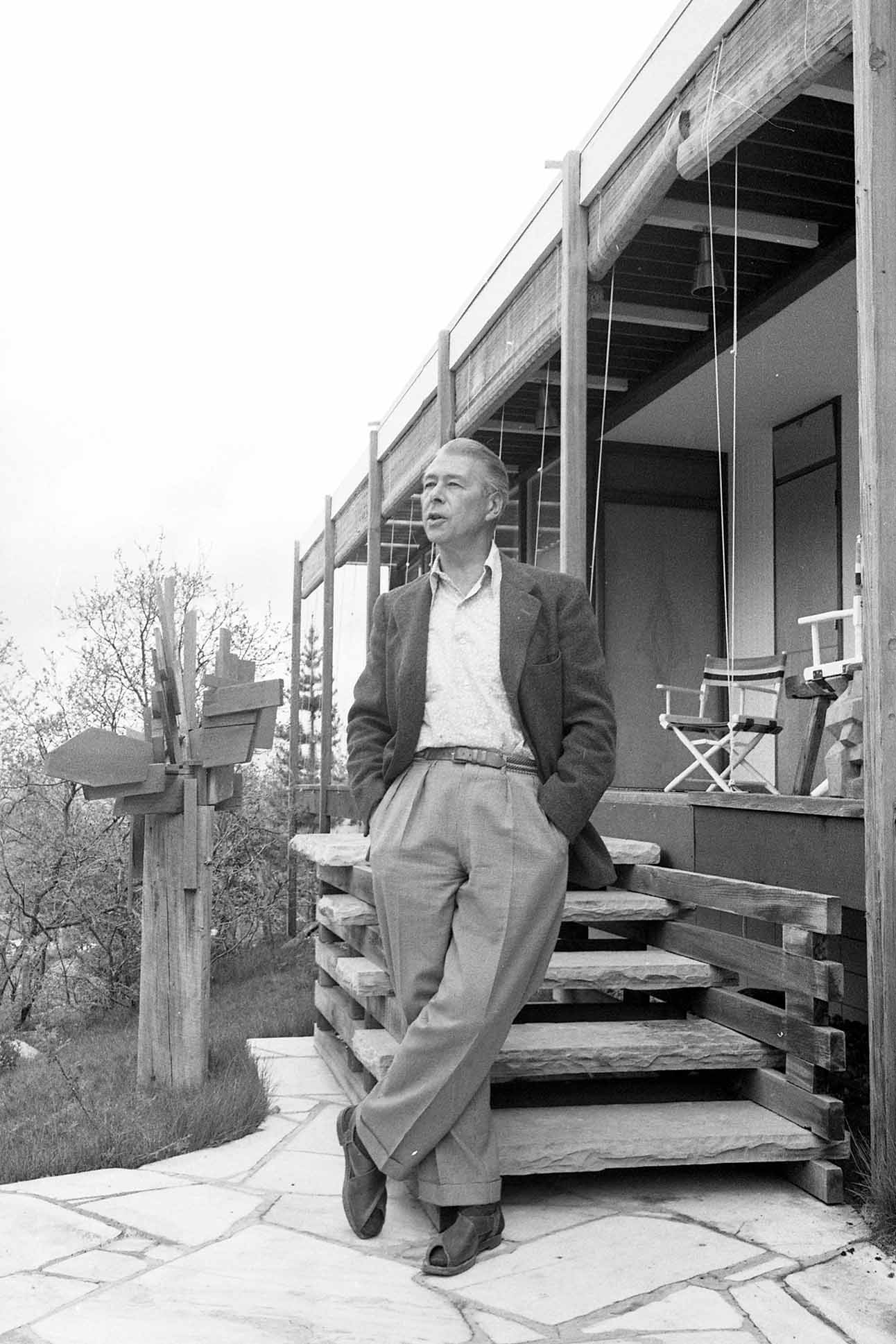

The following year, the Paepckes enlisted graphic designer Herbert Bayer, a Bauhaus disciple and German native who was planning to move back to Europe after the war. Walter convinced him to relocate instead to Aspen, luring him with vivid descriptions of the Colorado Rockies—or what he pegged as the American version of the Alps. Bayer was soon hooked and would go on to make some of the town’s first ski ads, which remain iconic visuals to this day.

Walter, along with a group of scholars, tested out the Aspen Idea for the first time in 1949, by staging a three-week bicentennial celebration of Goethe—the famed German poet, novelist, and playwright—in Aspen. He theorized that celebrating Goethe, who espoused emotionalism and humanism in his work, “could help heal the wounds of World War II,” according to Ballinger—and also bring Germany back into the cultural conversation. They invited other intellectuals and creatives of the day and commissioned architect Eero Saarinen to design the canvas tent where talks, panels, and musical concerts were held. The event was a success, drawing more than 2,000 visitors.

Reeling from their first event’s positive response, the Paepckes were ready to put Aspen on the map as both a cultural hub and a ski resort. They would go on to establish the Aspen Institute for Humanistic Studies (known today as the Aspen Institute), the Aspen Music Festival, and, along with the Austrian ski racer Friedl Pfeifer, the Aspen Ski Corp. (now the Aspen Skiing Company).

From 1953 to 1973, Bayer designed dozens of Bauhaus structures around town: seminar rooms, lecture halls, a health club, guest quarters, and residences across the Aspen Institute’s 40-acre campus. In keeping with Bauhaus principles, the buildings were pared down and modest, made with simple materials like concrete and steel, and featuring plenty of floor-to-ceiling windows to showcase the magnificent landscapes that surrounded the property. Another Bauhaus principle— that thoughtful design could affect social change—led to the design of contemplative spaces where guests could discuss big ideas in the morning, commune with spectacular nature in the afternoon, and then attend a concert in the evening, perhaps followed by more serious discussions late into the night, under the towering aspen trees.

It was the idealistic manifestation of the Paepckes’ intellectual utopia. “Aspen became a model of what the Bauhaus goal of integration of all the arts and design could accomplish,” says Gwen Chanzit, a curator at the Denver Art Museum and author of From Bauhaus to Aspen: Herbert Bayer and Modernist Design in America.

The Aspen Institute grew in popularity and attracted luminaries from all over the world. In 1951, it sponsored a photography conference attended by Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange. In 1962, it held one of the first conferences on the effects of global warming. And over the years, the institute and its various conferences have hosted everyone from Bill Clinton to Jane Goodall to Toni Morrison.

Bayer saw the campus as his Gesamtkunstwerk, a “total work of art,” but the designer also made an impact beyond the campus. He helped restore older buildings in town, like the Wheeler Opera House. When tasked with building something new, he set out in a more modern direction, a vision that established Aspen as an outlier among American ski resorts, becoming a contemporary mecca among the many faux Swiss chalet mountain towns.

In recent decades, that style has been embraced by more architects, whose modern glass, timber, and steel buildings are easily identifiable as Bauhaus-inspired: Studio B’s curving, stone Christ Episcopal Church; Charles Cunniffe’s Theatre Aspen, with its design-forward tent of a polycarbonate panels; and Shigeru Ban’s Aspen Art Museum, defined by striking wood cladding that envelops the building.

The legacy of the Paepckes, the Bauhaus movement, and the Aspen Idea live on today in the physical presence of these modern landmarks, in the original works of Bayer and his contemporaries, and the ideas they represented. This goes beyond the brick-and-mortar to the town’s busy cultural events calendar, year-round programming at the Aspen Music Festival and School, the Aspen Art Museum, and the Aspen Ideas Festival. Every summer, brilliant minds from around the globe gather to continue to shape the future—from progressive politicians, climate change experts, and scientists, such as John Kerry and Bill Nye, to actors and celebrities with their own passion issues, including Selma Blair and Brian Cox.

Modern Aspen’s founding mother and father would surely approve.

Bauhaus Landmarks

Take a tour of the iconic structures that embody—and are inspired bythe Paepckes’ utopic vision.

Aspen Art Museum

637 E. Hyman Avenue

The Aspen Institute

1000 N. 3rd Street

Christ Episcopal Church

536 W. North Street

Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies

610 Gillespie Avenue

Theatre Aspen

110 E. Hallam Street