Text by Lauren McNally

Images by John Hook

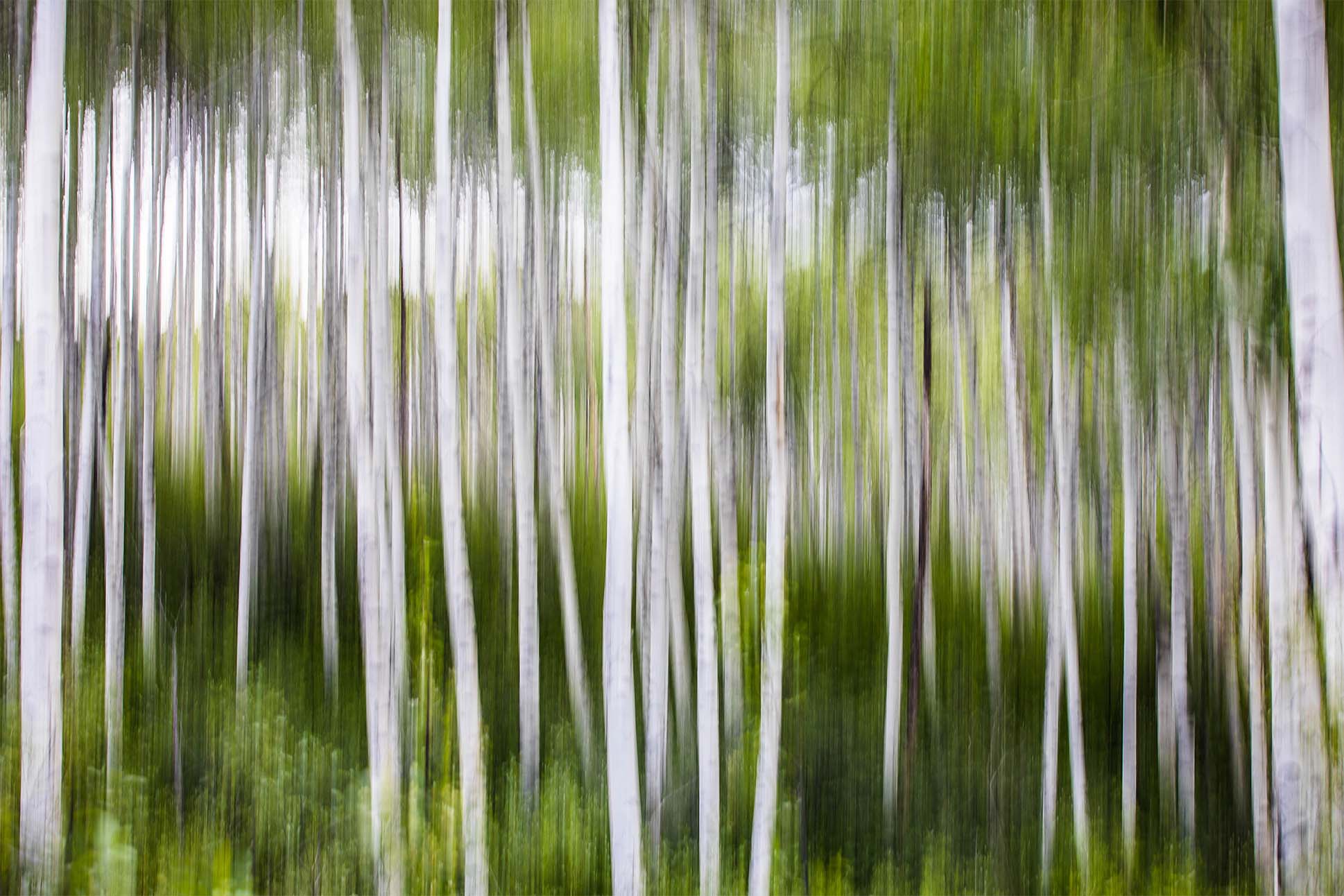

When I arrive at our meeting place, forest bathing expert Phyllis Look invites me into her “office”—a tree-shrouded gazebo just inside the entrance of a public botanical garden. It’s here where she explains that, despite the name, forest bathing doesn’t involve any water. The term refers to the therapeutic practice of soaking in the forest atmosphere and allowing it to nourish mind, body, and soul.

The recent retiree began leading forest bathing walks after training with the Association of Nature and Forest Therapy Guides and Programs, an organization that has certified approximately 2,000 forest therapy guides in 60 countries since its founding in 2012. As we amble across a sunny, sloped lawn dotted with birds dipping their beaks in the grass, Look is careful to specify that she’s a guide, not a therapist or scientist. It isn’t her goal to convince anyone of the benefits of forest bathing, she says, though decades of research into the practice show compelling findings.

Forest bathing has been around since the 1980s, an answer to the culture of toxic productivity that emerged in Japan during the country’s rapid economic growth after World War II. To address the rise in chronic disease and a phenomenon known as karoshi, or death by overwork, the Japanese government launched a public health campaign to promote forest bathing, or shinrin-yoku. Today, there are more than 60 government-supported forest-therapy bases throughout Japan. Rooted in the notion that humans are wired to thrive in natural environments, forest bathing and other forms of nature therapy are gaining traction around the world as a means to cope with the stresses and mental fatigue of modern, urban life.

Advocates of forest bathing often regard nature as both sentient and sacred.

“I think slowness is the key,” Look says, pausing to present the first of several guided exercises in her forest walk. She refers to these exercises as “invitations.” In an invitation she calls “pleasures of presence,” I’m meant to anchor myself in the present moment through mindful engagement of the senses. “It’s as if you’re a connoisseur of grass,” she says, sipping the air through pursed lips. “Taste the oils in the grass and swirl them around in your mouth. Bring your nose closer to the ground and inhale the secret aroma inside of that dried leaf or those pebbles of dirt. If any of these bring you pleasure, be with that pleasure. Give yourself over to it.”

The pleasure evoked by the smell of cut grass, the breeze on our skin, or the murmur of a distant stream isn’t just in our heads. Researchers have found that people who spend at least two hours per week in nature demonstrate a number of physiological changes, from reduced blood pressure and lower levels of the stress hormone cortisol to improvements in immune function and cognitive performance. In Japan, one of the most densely forested countries in the world, studies have centered on the effects of being around trees—namely, the disease-fighting properties of phytoncides. These airborne compounds, emitted by trees and other plants as defense against harmful microorganisms, are also shown to activate cancer-fighting cells in humans. One study discovered the anti-cancer benefits of phytoncides last up to 30 days after a three-day immersion in nature.

You don’t need a guide to go forest bathing, Look says, but there is value in forest bathing with someone dedicated to your rest and relaxation. A guide can watch the clock, for example, so you don’t have to. “Time is very flexible,” my guide muses amid preparations for a tea ceremony, the last portion of our forest bathing session. “You can completely let go, and that’s really restful for the brain.” It’s fitting, she reasons, that the Japanese kanji for “rest” appears to be a combination of two others: the symbol for “person” and the one for “tree.”

Naturalists from the Aspen Center for Environmental Studies share their go-to destinations for forest bathing in the Roaring Fork Valley.

Hunter Creek

The Hunter Creek area is a favorite of mine to quickly go from my human-dominated life of work and family to a relaxed state of being in nature. Very quickly, the sound of the creek and the cover of the trees change my mental state.

There are plenty of places to step off the trail and allow your mind to wander. Sometimes I’m drawn to something natural, like an insect or a strange spot on a leaf, and I let thoughts bounce around in my head. Sometimes I contemplate a problem and see things in a different way. New, creative ideas come up out of the blue.

Hunter Creek is generally south facing, so it stays warm during all seasons. It has diverse vegetation, from huge cottonwoods to spruce and fir. It has shrubs like oak and serviceberry, and all of the birds and animals that accompany them. There are also relics from the past—I like to look for blast marks in the rocks, where early settlers forged a path.

It’s a place I’ve been to hundreds of times, and though it is comforting in its familiarity, I uncover new insights every time I go.

— Jim Kravitz, Director of Naturalist Programs

Gold Butte

On long summer afternoons, there’s still time to go rock climbing after work at Gold Butte, if you hurry. A friend and I once biked down Cemetery Lane already in our harnesses—she carried the rope coil tied into a backpack and I brought everything else. From the far edge of Gold Butte, we watched a storm roll in. The valley overflowed with heavy clouds from the north. We watched people walking by the river beneath us, disappearing into mist, and yet when I gazed south, I found blue sky and Independence Pass lit by sunshine. From Gold Butte, the valley looked as wild and tucked away as the day I first saw it.

Gold Butte is covered in Gambel oak and sagebrush and sunlight. Geologically, it’s composed of Entrada sandstone, sediment deposited around an ancient interior seaway as its shoreline approached and receded. In Aspen, the exposed yellow cliffs jut out over the Roaring Fork like the prow of a ship. In Utah, the same rock forms part of Arches and Canyonlands National Parks. Being at Gold Butte makes me feel connected to the Grand Staircase of geologic units that link the Southwest.

— Grace Berg, Naturalist

North Star Nature Preserve

One of my favorite places to find quiet in the valley is North Star Nature Preserve, a section of land just east of town with trails fit for walking, running, or biking along a mellow section of the Roaring Fork. North Star Nature Preserve is easily accessible, but because of noise restrictions, it stays peaceful all year round. Whether you’re looking to paddle board on a hot day or go for a run on a brisk morning, North Star has so much space and beauty to offer.

Because it’s protected, there are so many ecological tokens you can find, especially on foot. The wildflowers that grow along the trail are diverse and gorgeous. The local moose, when given proper distance and space, are spectacular to view. The wide valley that was carved out by glaciers long ago offers a unique, open view of the surrounding mountains.

As with any place in nature, but especially in a preserve, be considerate of the flora and fauna living there. Stay on trail, check water levels if you’re paddle boarding so that you don’t disrupt the riverbed, and—my biggest tip—try to stay quiet to notice the environment around you.

— Cecily Nordstrom, Naturalist