By Camille Okhio

“The root function of language is to control the universe by describing it,” James Baldwin wrote in his 1953 essay, “Stranger in the Village.” In the essay, which serves as one of the pillars of artist Glenn Ligon’s decades-long practice, Baldwin meditates on the self-deception required to believe in and enact white supremacy, and how, “by means of what the white man imagines the black man to be, the black man is enabled to know who the white man is.”

Baldwin’s incisive observations and gorgeous language at first seem at odds: How can you read about the profound evil enacted by racists and somehow enjoy the experience? But read enough of his work and you come to understand that he could not have made his points so effectively without his deft handling of the English language.

Like Baldwin, Ligon employs dueling factors to create seamless, focused art. His text paintings, which he’s made since the late 1980s, directly quote Richard Pryor, Toni Morrison, Zora Neale Hurston, Ralph Ellison, and, naturally, Baldwin, with Ligon repainting each letter from left to right using coal dust, ink, and stencils until each word is all but obscured.

“My work has always, in some ways, been about the struggle to communicate,” he says. “My paintings are hard to read—and that is kind of the point. Those texts [I refer to] are dealing with difficult, weighty subject matter, so looking at them should be difficult and complicated.” You could argue that this painterly approach, which forces the observer to squint to decipher the message, is Ligon’s own bid for control.

Offset prints, 78 text pages

Each framed: Prints 11.5 x 11.5 inches (29.2 x 29.2 cm); text pages 5.25 x 7.25 inches (13.3 x 18.4 cm)

Photographer credit: Ronald Amstutz © Glenn Ligon; courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Thomas Dane Gallery

Silkscreen ink and gesso on canvas

82 x 144 inches (208.3 x 365.8 cm)

Photographer credit: Brian Forrest © Glenn Ligon; courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Thomas Dane Gallery

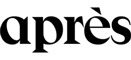

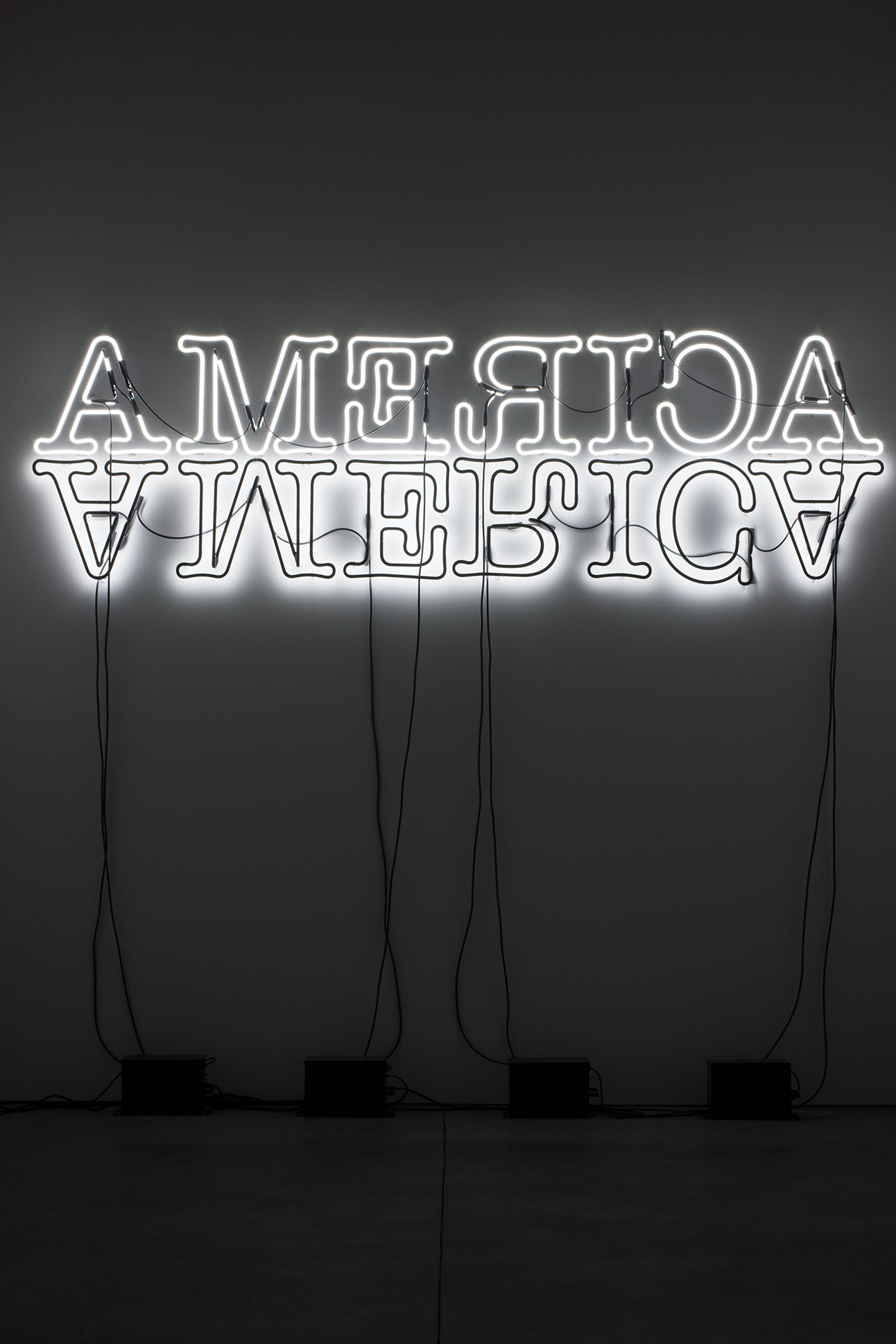

Neon and paint

36 x 192 inches (91.4 x 487.7 cm)

Photographer credit: Thomas Barratt © Glenn Ligon; courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Thomas Dane Gallery

Gifted since he first started forming words, Ligon’s kindergarten teacher in the South Bronx begrudgingly accepted that he far surpassed his peers, telling his mother, “Your kids might be smart here, but they will be average at a real school,” Ligon recalls. Undeterred, his mother placed him at Walden School in New York’s Upper West Side, where he thrived. After-school drawing classes at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and pottery classes in Greenwich Village refined the young Ligon’s eye and hand; four years at Wesleyan University continued the process. But it was in 1989, when the National Endowment for the Arts gave Ligon a grant to pursue drawing, that he first began to see himself as an artist with a capital A. “I thought, the government thinks I’m an artist, so I guess I can say I’m an artist now,” Ligon says. The next decade was one of immense creative and intellectual growth.

With text-based paintings, Ligon has demanded raw, honest contemplation—from both himself and his audience. “My work is a conversation,” he says. His demeanor, like his practice, appears initially gentle. The intensity of his works is revealed bit by bit the longer you look and the harder you squint.

The man himself is straightforward, simply dressed, often in black and white—the colors that dominate his work. He sets certain rules for himself so that he can break others, thinking often about the legal and social structures that limit large swathes of Americans’ freedoms. “Rules give me a starting place and structure that I then break,” he says. “Once rules become too strict and codified, you stop allowing things to happen. The work I’m most interested in is what comes out of mistakes.”

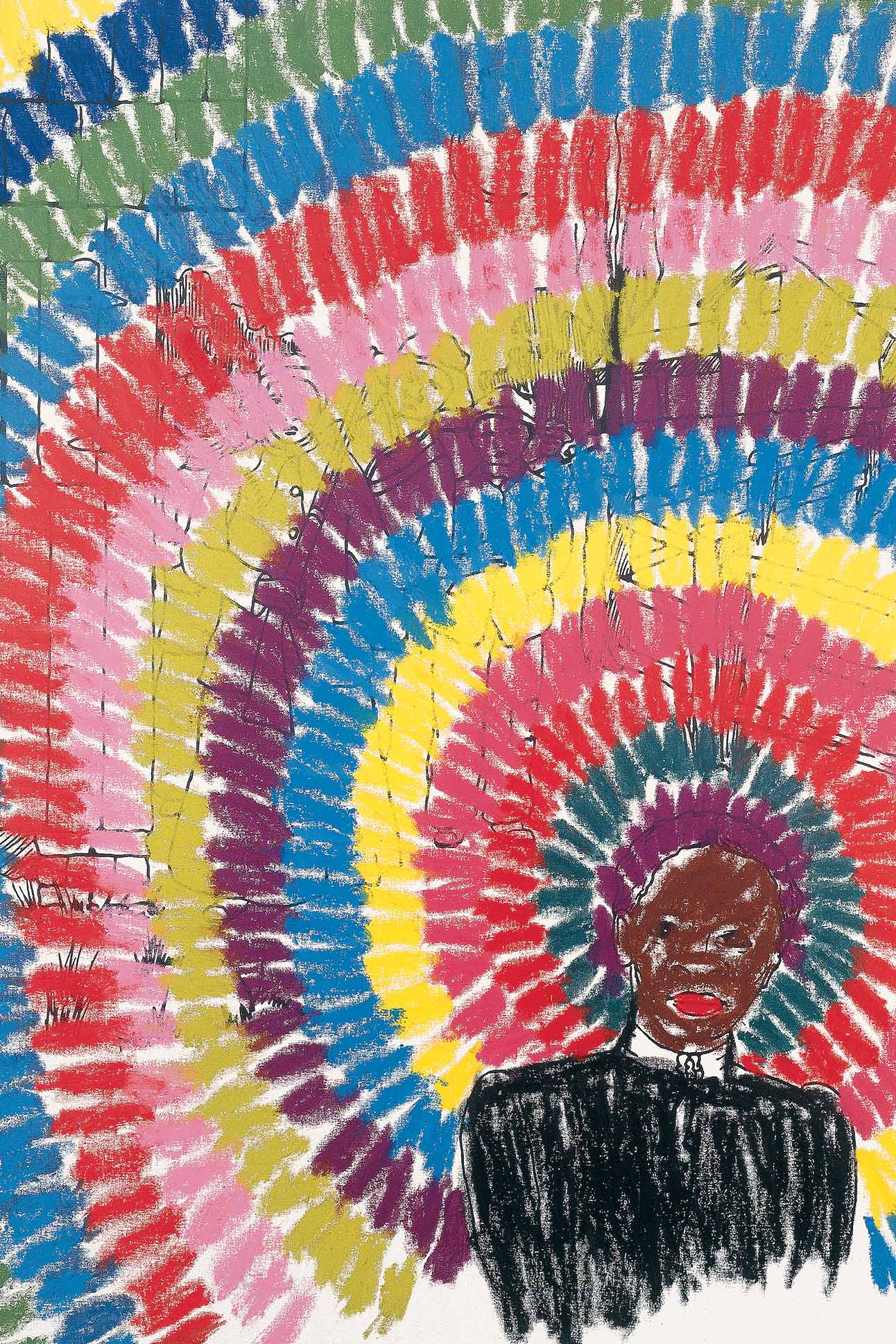

Oil stick, coal dust, and acrylic on paper

12 x 9 inches (30.5 x 22.9 cm)

Photographer credit: Ronald Amstutz © Glenn Ligon; courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Thomas Dane Gallery

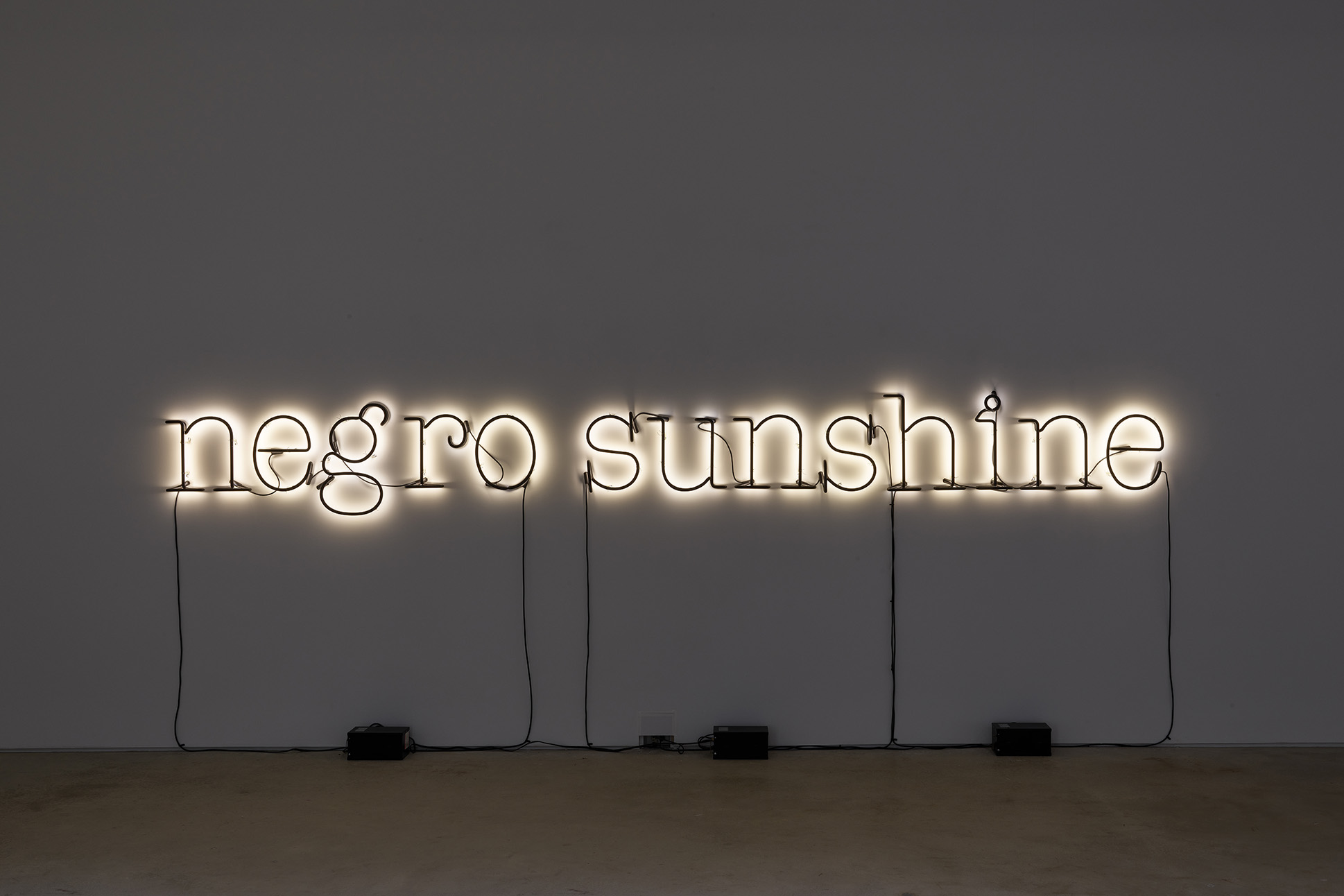

Carbon and graphite on Kozo paper

15.75 x 11.75 inches (40 x 29.8 cm)

Photographer credit: Ronald Amstutz © Glenn Ligon; courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Thomas Dane Gallery

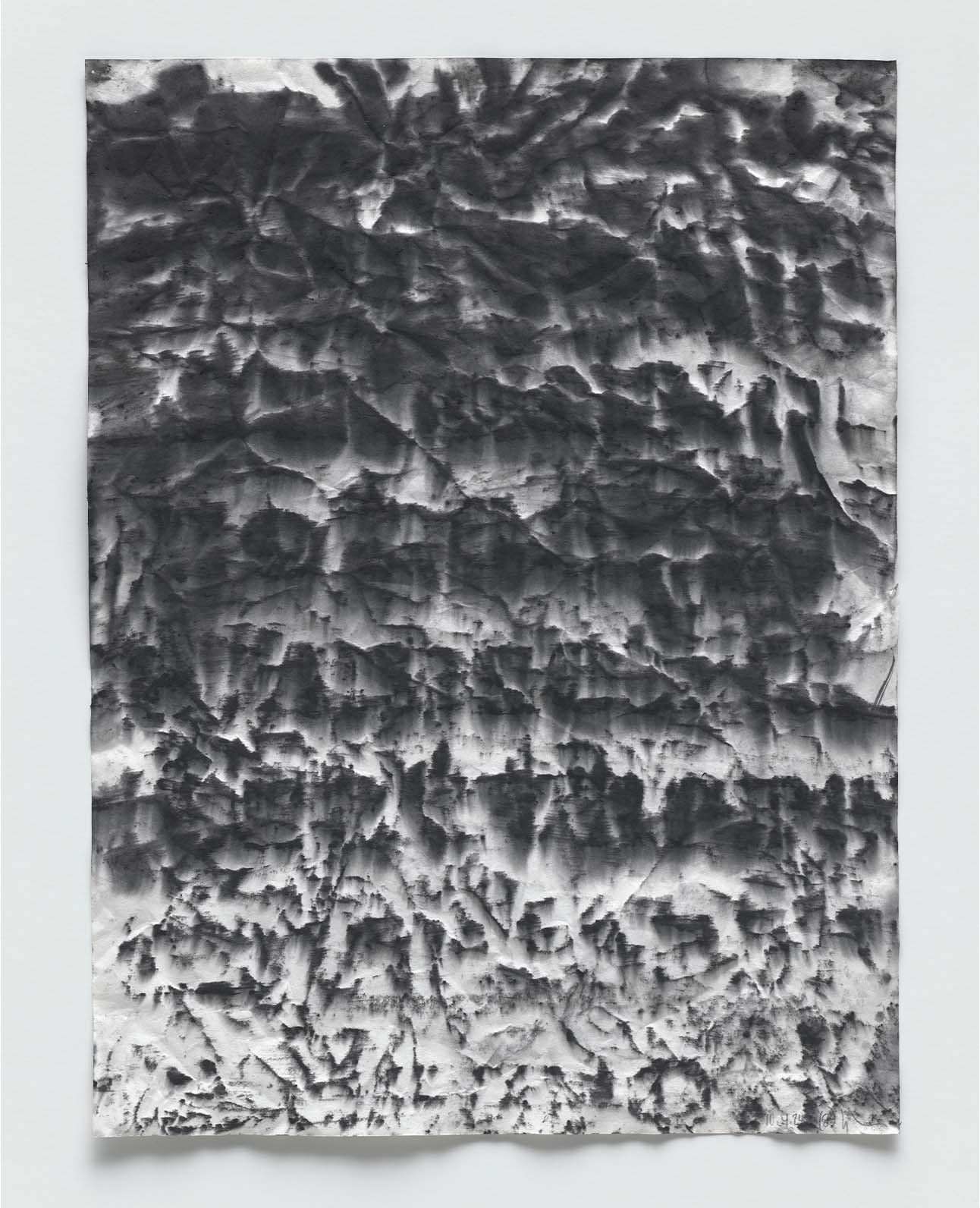

Silkscreen, coal dust and acrylic on canvas

16 panels, 41 x 32.5 inches (104.1 x 82.6 cm)

Photographer credit: Sarah Muehlbauer © Glenn Ligon; courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Thomas Dane Gallery

In December 2025, Ligon’s masterly mistakes will fill the galleries of the Aspen Art Museum in the artist’s first solo exhibition with the institution. “It’s hard to believe that America, Glenn’s mid-career survey at the Whitney, was presented nearly 15 years ago,” says Daniel Merritt, Aspen Art Museum’s chief curator. “He is an artist whose influence and reach upon younger generations is just beginning to be understood. There remains so much to unearth in Glenn’s work, and Aspen Art Museum is thrilled to bring these new considerations to light.” Indeed, the survey will be the artist’s first institutional solo show of this scale since that landmark exhibition opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art in 2011.

During ArtCrush week this summer, Ligon will receive the Lewis Family Art Award, which will be presented alongside programming at the Aspen Art Museum that focuses on his work and its topics. “Glenn is one of the most important artists in America today,” Merritt says. “He has built a deep, influential legacy and has emerged as a north star for subsequent generations of artists.”

Ligon’s practice has spanned many mediums, from sculpture to sound to curation itself. His two-person show at 52 Walker in Manhattan earlier this year paired his neon sculptures with a score by the late composer Julius Eastman, and he took part in organizing Okwui Enwezor’s Grief and Grievance at New York City’s New Museum in 2021. His exhibition at the Aspen Art Museum will focus on his works on paper, along with his prints and multiples.

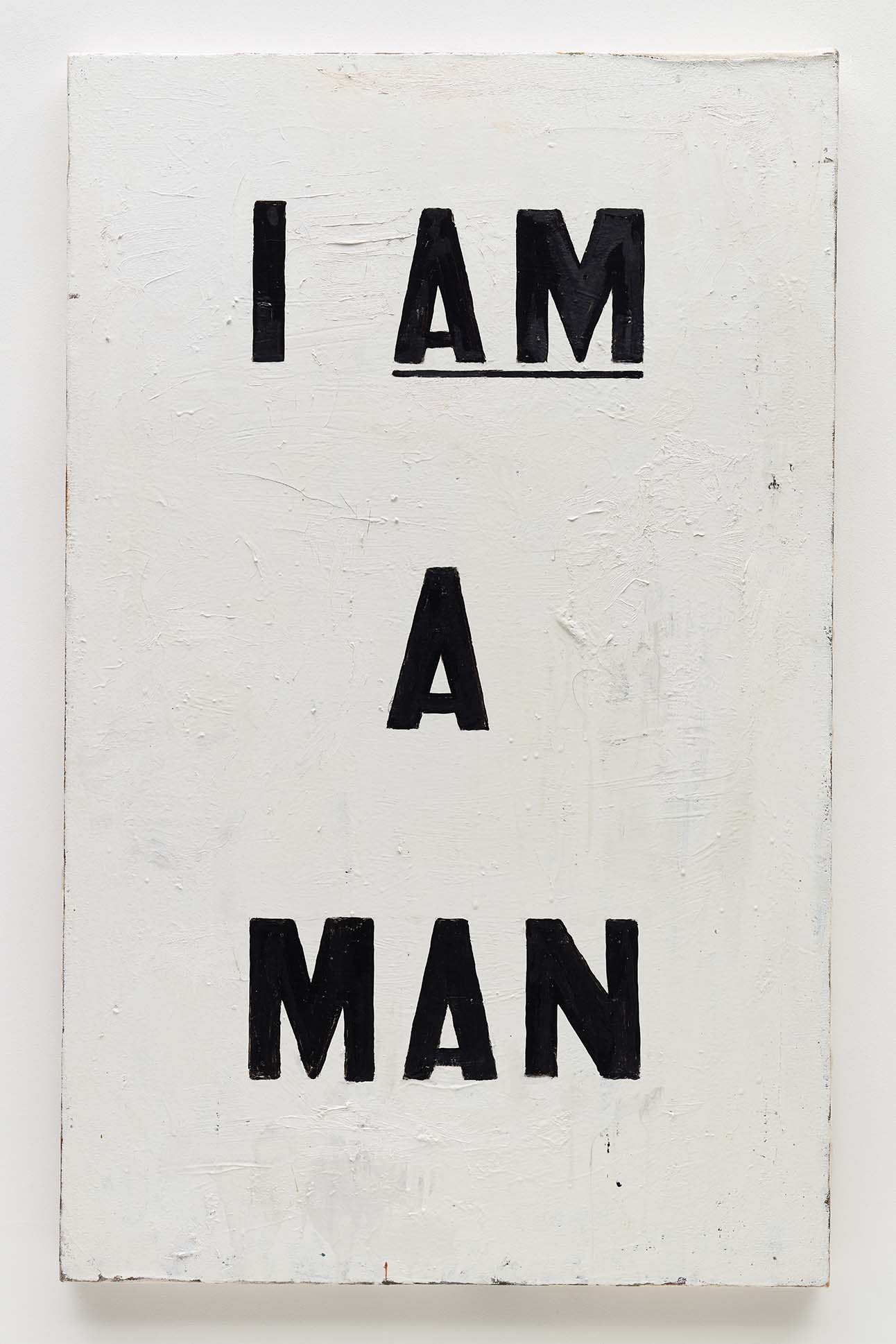

Silkscreen ink, oil stick, and gesso on canvas

48 x 36 inches (121.9 x 91.4 cm)

© Glenn Ligon; courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Thomas Dane Gallery

Oil and enamel on canvas

40 x 25 inches (101.6 x 63.5 cm)

Photographer credit: Ronald Amstutz © Glenn Ligon; courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Thomas Dane Gallery

Neon and paint

36 x 120 inches (91.4 x 304.8 cm) Edition of 3 and 2 APs

Photographer credit: Farzad Owrang © Glenn Ligon; courtesy of the artist, Hauser & Wirth, and Thomas Dane Gallery

“Glenn possesses a remarkable openness to the world,” Merritt says. “Culture flows through him. There is an alertness, but also a wry amusement to the ways in which he sees the work. Artists with a wicked sense of humor, like Glenn, tend to make very potent art.”

As serious as he is funny, Ligon avoids attention, preferring any honors he may receive to funnel back into his work or to serve society in some way. He is reserved in public, observing everything around him, taking mental notes, and later highlighting the lessons that still need to be learned. “Glenn is an artist who is skilled at processing turbulence and tumult, and in these very unsteady times, there is power in turning to the past,” Merritt says. “Glenn can identify the poetics in that.”

The power of a word is generally in its ability to be understood. Somehow, Ligon has inverted that power, allowing for a word to hold value in its indecipherability. He is a soothsayer, with a preternatural understanding of what will come, informed by his thorough knowledge of what has come before. And, with that knowledge, he catalyzes the contemporary landscape of the art world—and American society at large. “As Baldwin said,” Ligon notes, “artists are disturbers of the peace.”