Text by Andrew Travers

Images by Tamara Susa, Trevor Triano, and courtesy of Aspen Historical Society and Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies

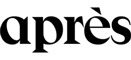

Artist, designer, and polymath Herbert Bayer molded the physical and cultural landscape of Aspen over the course of its three most formative decades. As a young artist in the 1920s, Bayer studied and then taught at the influential Bauhaus school in Germany before embarking on a successful graphic design practice. He fled Nazi Germany for the U.S. in 1938 and immediately organized a Bauhaus exhibition for the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where he first came to the attention of industrialist-philanthropists Walter and Elizabeth Paepcke.

Arriving in Aspen in 1946 to work with the Paepckes to shape the utopia they envisioned there—one grounded in the “Aspen Idea” of elevating mind, body, and spirit—Bayer applied his multidisciplinary genius to imbue the depopulated silver-mining town with the Bauhaus school’s creative ideal of a “total work of art.” “What the future of Aspen promised then was the participation in shaping an environment,” he wrote in 1967. “This was one of my motives in choosing Aspen as a place to live and work.”

Today, Bayer’s influence can be felt on the idyllic campus pathways and in the inspiring gathering spaces he conceived for the Aspen Institute, and in the Bauhaus-inspired architecture that still peppers Aspen. And when the Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies opened its doors in 2022, a new generation of Aspenites and visitors were introduced to his wide-ranging creative genius.

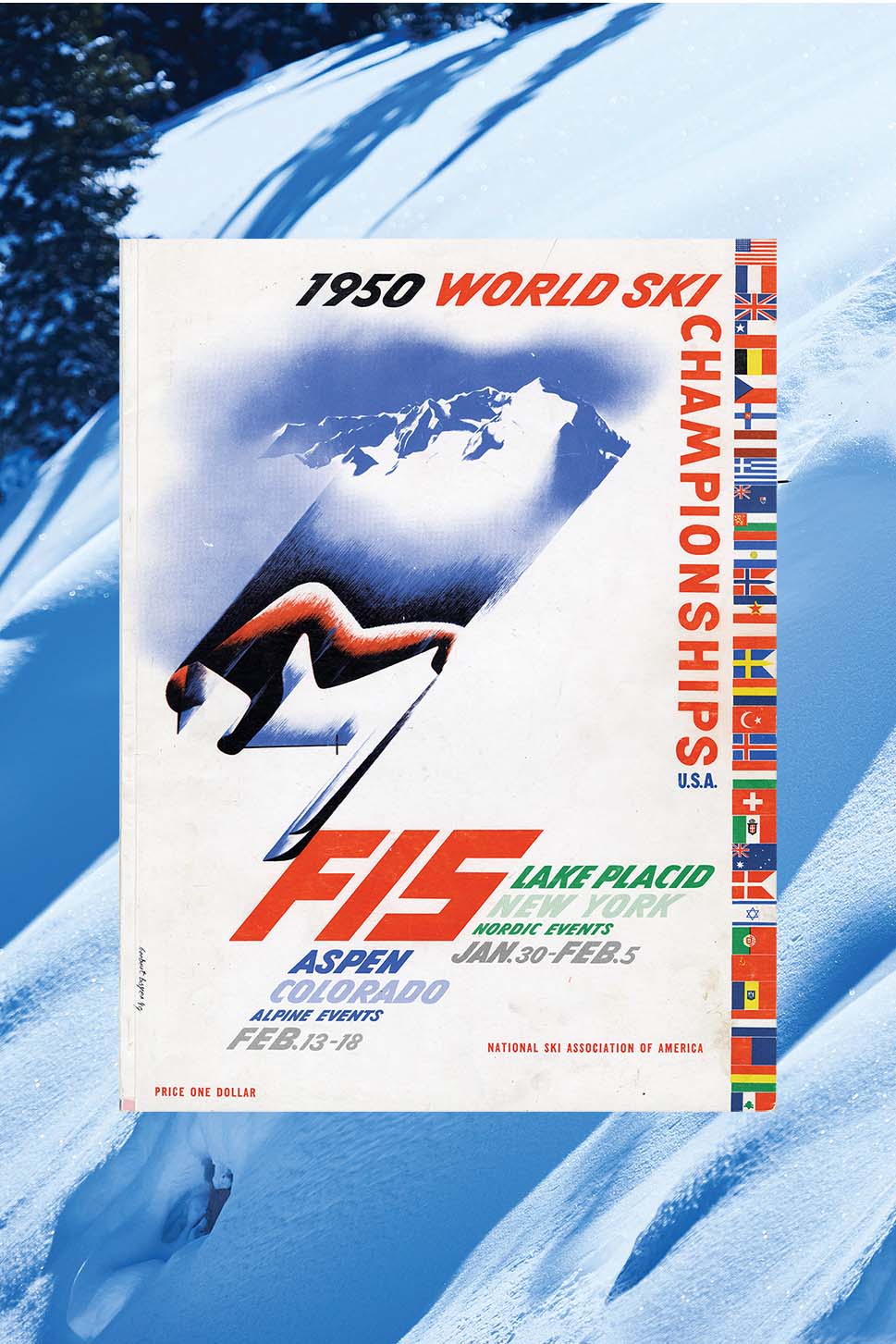

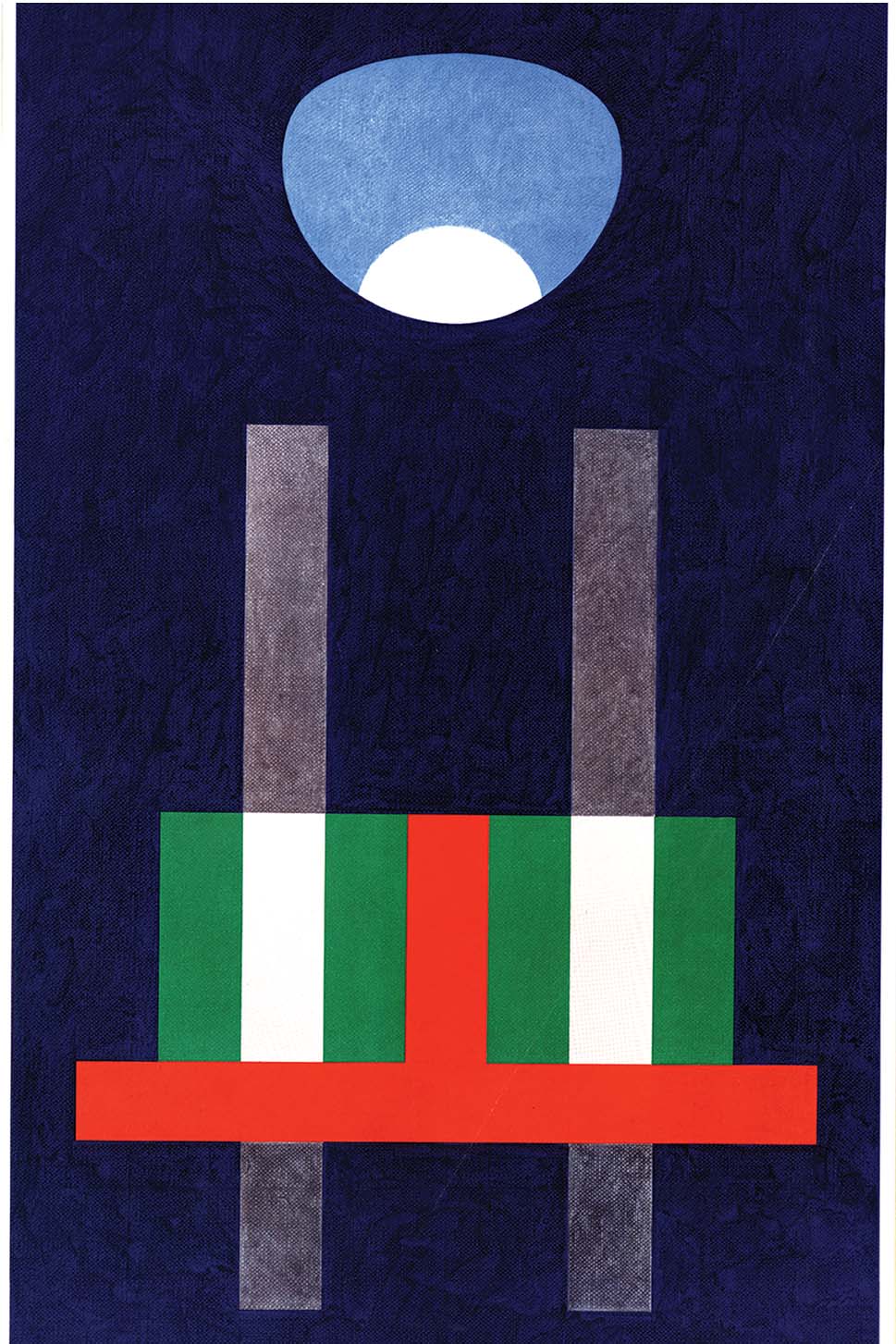

Born in the Alps, in Haag am Hausruck, Austria, in 1900, Bayer was a lifelong skier and mountaineer whose passion for the alpine lifestyle naturally made its way into his work. During a winter stay in Stowe, Vermont, in 1944, Bayer began his Mountains and Convolutions series, which exploded with inspiration upon his move to Aspen—combining Bayer’s study of geology, cartography, and geometry as he began viewing mountainscapes as living, moving organisms that evolved through the ages.

“I saw the mountains not in their textured and detailed shapes, but suddenly saw them as expressions of interior forces, as undulating forms whose motion is caused by forces of time and geology,” Bayer explained in a 1973 interview. “Of course, we do not see this motion, but if we could make a time-lapse painting of mountains stretched over millions of years, we would see this motion.” The series included paintings, tapestries, and other mediums but culminated in Bayer’s etched sgraffito mural on the side of the Koch Seminar Building, completed in 1953 as his first structure on the Aspen Institute campus.

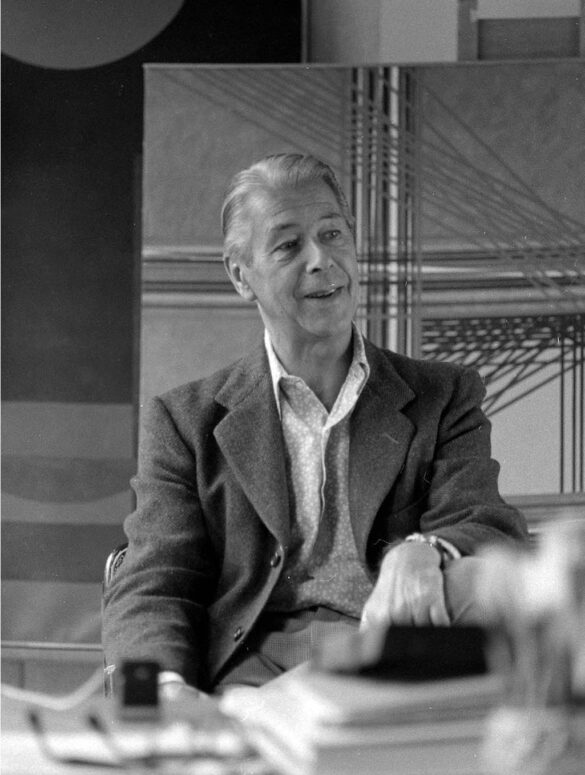

“The artist needs business, and business needs useful art,” Bayer said at the inaugural Aspen Design Conference in 1950. To that end, Bayer used art to market Aspen as a destination. He designed Aspen Ski Corp.’s original aspen-leaf logo, pins, and event programs to promote tourism and crafted the first posters championing the town’s ski hills, including the now-iconic “Ski in Aspen” designs that collaged alluring photos and illustrations of skiers and fixated on the interconnecting “S” and “8” lines carved in the snow as they link turns.

While championing historic preservation and serving as a planning commissioner in Aspen, Bayer also placed his stamp on the traditional white picket fence. The “Bayer fence,” with its crenelated tops in the style of castle battlements, was once commonplace in Aspen’s West End, enclosing the yards of restored Victorians like Bayer’s home on West Francis Street, where a restored Bayer fence still stands.

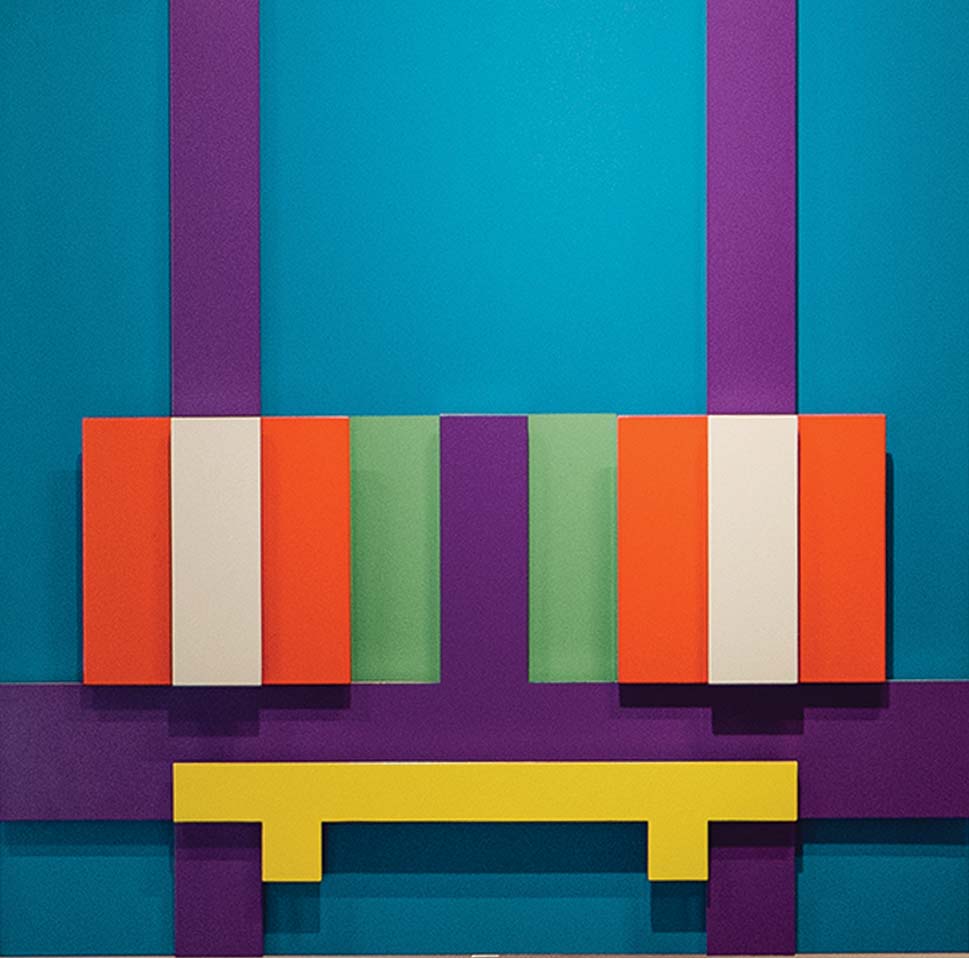

Bayer’s devotion to functionality and his sense of whimsy are embodied in his Kaleidoscreen, a seven-foot-tall, 12-foot-wide aluminum sculpture with seven multi-colored adjustable panels that fit together like a jigsaw puzzle and are meant to open and close with a hand crank. Completed in 1957, this louvered aluminum screen originally provided shade for sunbathers at an Aspen Meadows Resort swimming pool. Today it sits beside the Walter Isaacson Reception Center at a trailhead leading to the Roaring Fork River. The Bayer Center is soon to embark on a $73,000 critical restoration of Kaleidoscreen.

Bayer’s masterpiece is the Aspen Institute campus itself. Across more than two decades, Bayer designed its buildings, landscape, sculptures, and earthworks. Here Bayer visually explored the earth, light, shadow, and humanity’s place in the world with physical manifestations of ideas he had first investigated on canvas. Bayer described his approach to permanent works like Grass Mound (1954), Marble Garden (1955), and Anderson Park (1973) as “an inquiry into the reality of space rather than painting the illusion of space on a two-dimensional plane.”

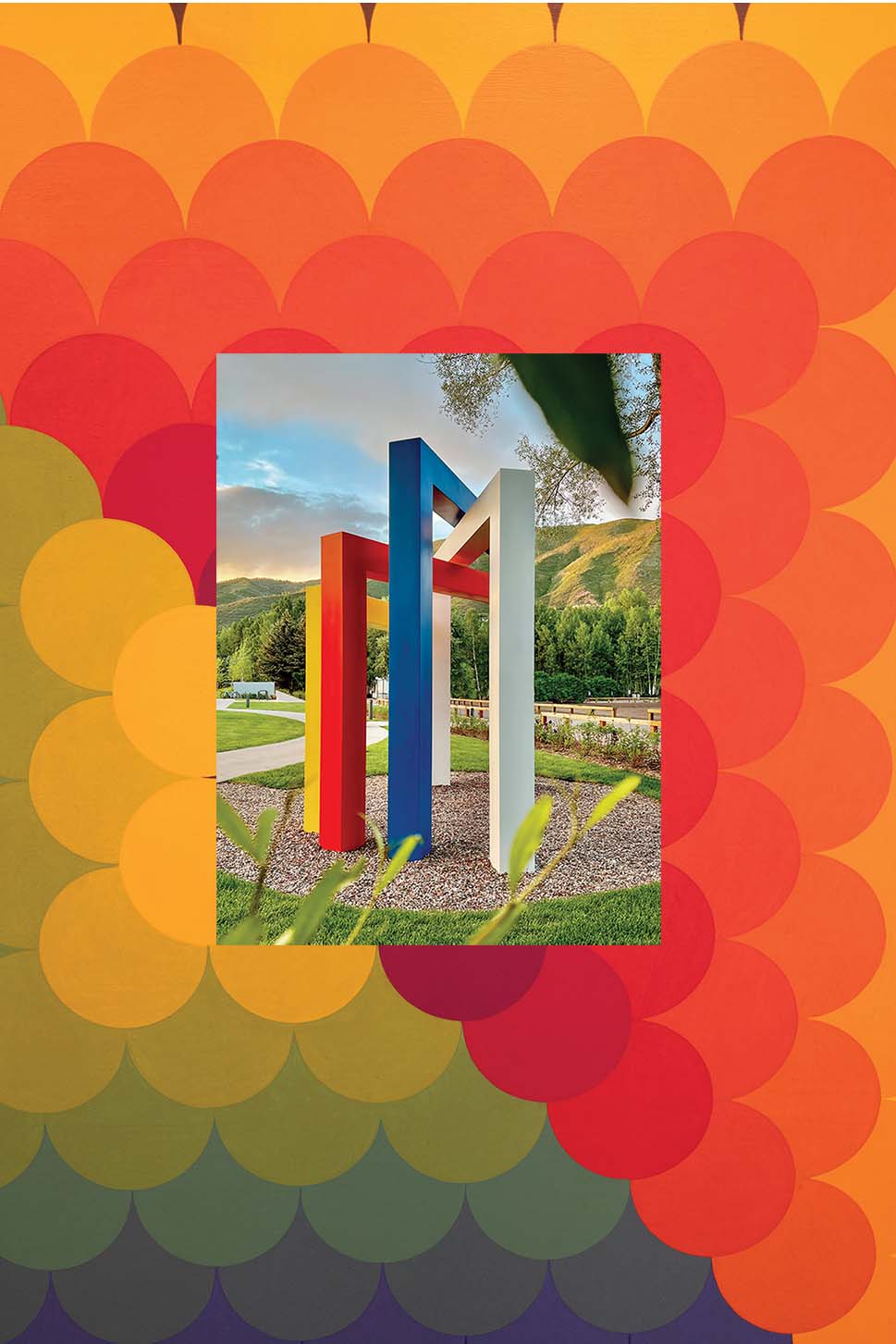

The Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies, opened in 2022 on the southern Gillespie Avenue border of the Aspen Institute’s 40-acre campus, gives the artist’s work a permanent home, with more than 7,000 square feet of gallery space to host rotating exhibitions. Designed by Jeffrey Berkus Architects and Rowland+Broughton, it draws inspiration from Bayer’s architectural work and rigorous attention to geometries, paying homage to Bayer’s visual explorations of the Fibonacci mathematical sequence in its curving entrance pathway. The free museum welcomes visitors with Bayer’s 16-foot-tall Four Chromatic Gates, a set of four nested steel rectangles painted primary yellow, red, white, and his signature “Bayer blue.”

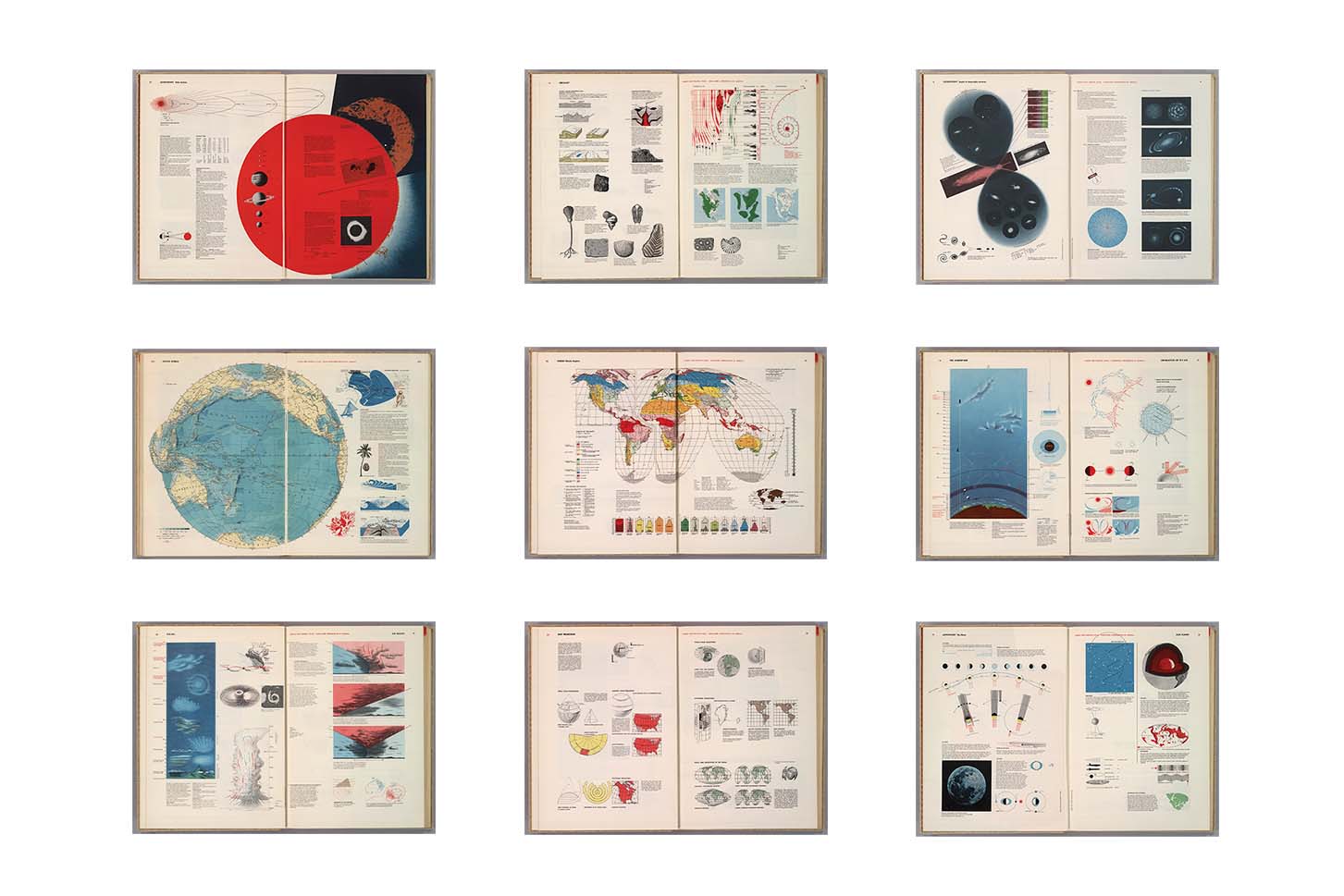

Bayer’s 1953 World Geo-Graphic Atlas changed the course of popular scientific illustrations and data visualization. The book, the subject of multiple exhibitions at the Aspen Institute and its Resnick Center for Herbert Bayer Studies in 2023, unified Bayer’s multidisciplinary practice as artist, designer, and communicator. As historian Benjamin Benus puts it in his new book, Herbert Bayer’s World Geo-Graphic Atlas and Information Design at Midcentury, the atlas “represented a continuation—even a culmination—of projects with which he had been engaged from the earliest stages of his career” when he was a student at the Bauhaus in prewar Germany.

Bayer’s hyphenated title was quite intentional, emphasizing his graphic visual presentation of geography, geology, demography, astronomy, climate, and economics in an artful rebuke of the text-heavy, “letter-poisoned” approach of conventional atlases and encyclopedias. The product of five years of research, collaboration, and creation, the atlas includes stunningly original Bayer artwork and more than 4,000 illustrations.