Text and images by Kersten Vasey Bowers

Film stills courtesy of Resistance Climbing

Andrew Bisharat believes his best climbing days are behind him. A former die-hard climber, the father of two admits to spending less time lately giving his favorite sport routes a burn at his local crag of choice (Rifle Mountain Park) and more time burning through repeat viewings of How to Train Your Dragon. Alluding to a rotator cuff injury that sidelined him for seven months, he jokes, “I’m kind of in that middle-aged phase of life when I wonder if I should just give up everything I love.”

Bisharat’s disillusionment from climbing comes after more than 20 years consumed by a love for the sport. His long career in climbing saw him advancing to harder and more impressive climbs while nurturing his passion for climbing as an accomplished writer and editor, working as a senior staffer for the climbing publication Rock & Ice and covering adventure sports for National Geographic, The New York Times, and Outside magazine. (He also runs the popular climbing website Evening Sends and co-hosts The RunOut Podcast with friend and Carbondale climber Chris Kalous.)

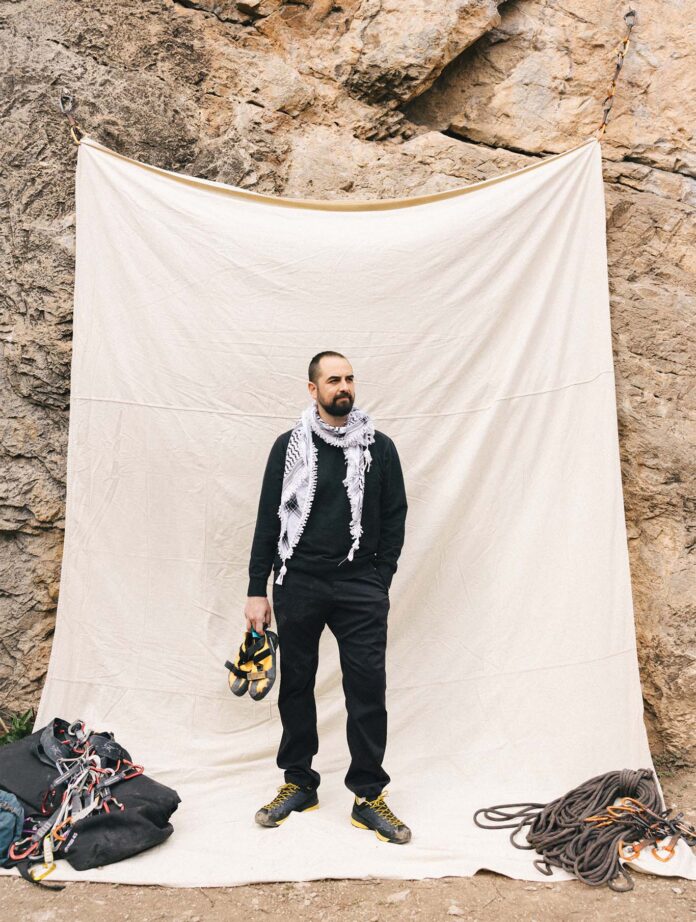

Over the years, Bisharat had been approached by several filmmakers interested in working together, but none of their proposals were as compelling as the one that came from outdoor adventure film company Reel Rock and climber Tim Bruns, an American who lived in the Israeli-occupied West Bank of Palestine from 2014 to 2017. Bruns had moved there partly to begin developing the limestone walls he’d scoped during travels to Palestine while studying abroad in Jordan. He introduced many locals to climbing, hosted regular climbing meetups, and established the West Bank’s first climbing gym, Wadi Climbing—later turning the gym over to the locals. “He just genuinely believed in the power of climbing,” Bisharat says.

After consulting with friends and relatives, Bisharat realized that teaming up with Bruns to document the West Bank’s budding climbing scene was a rare opportunity for the rest of the world to see Palestinians as they might see themselves: as climbers, as friends, as real people. For Bisharat, it was also an opportunity to bear firsthand witness to Israeli occupation of his ancestral homeland, and to finally visit the place his grandfather was exiled from during the 1948 Nakba, when hundreds of thousands of Palestinian Arabs were violently displaced by Zionist militias and Israeli armed forces during the Arab-Israeli war.

But the project wasn’t without its risks. At one point in the film, an interview with Hiba Shaheen, president of the Palestine Climbing Association and a regular at the climbing area at Ein Fara, is interrupted by the sound of gunfire. The interview ends, and the crew begins the long hike back around the adjacent Israeli settlement, one of many that dominate the West Bank.

Later, viewers meet Faris Abu Gosh, a local climber named after Faris Odeh, the 14-year-old boy who became a symbol of Palestinian resistance after he was photographed throwing a rock at an Israeli tank during the Second Intifada in 2000, and who was made a martyr when he was later shot and killed by an Israeli soldier. “I don’t want to end up like that,” Abu Gosh says in the film. “I can’t always just be fighting. I want to live as well.”

As the crew delved deeper into how Israeli occupation affects daily life for the film’s Palestinian subjects, the project evolved from a climbing documentary to a story about the resilience of the human spirit. “There’s an act of resistance inherent in every single aspect of life in Palestine,” Bisharat says.

Violence has since increased sharply in the West Bank. Many of the walls featured in the film are no longer safe to climb. Resistance Climbing likely couldn’t have been made after the attacks of October 7, 2023. Bisharat went into the project questioning his devotion to climbing, and he admits he feels some of that same ennui as the indisciminate killings continue in Palestine. Still, he is encouraged to see how the sport has changed the lives of the Palestinian climbers he befriended. Several were able to travel to the U.S. for screenings of the film in 2023, and together they climbed all over Colorado, cooked Palestinian food, and—in true American fashion—spent hours in Target.

After all, Resistance Climbing is as much about the will to live as it is the will to climb, full of laughter and celebration, affection and camaraderie. In one scene, Abu Gosh is seen dancing the tango, a passion he indulges when he isn’t meeting the West Bank group for climbs at their home crag. They still climb together every Friday—to gather, to cope, to feel free.