By Daliah Singer

Photography by Trevor Triano & Courtesy Stranahan’s

Denver was built on the idea of a good drink. Or, at the very least, a strong one.

Founded in 1858, the city began at the confluence of the South Platte and Cherry Creek rivers. Prospectors camped in the area before continuing west and were sold hooch by “enterprising individuals,” says Jake Norris, a Denver-based craft distillery consultant. “The first businesses in Colorado were bars.”

Saloons sprouted up across the soon-to-be state (Colorado was officially designated in 1876), serving miners who made their way here seeking silver and gold. In fact, the world’s largest silver nugget was harvested from Aspen’s Smuggler Mine.

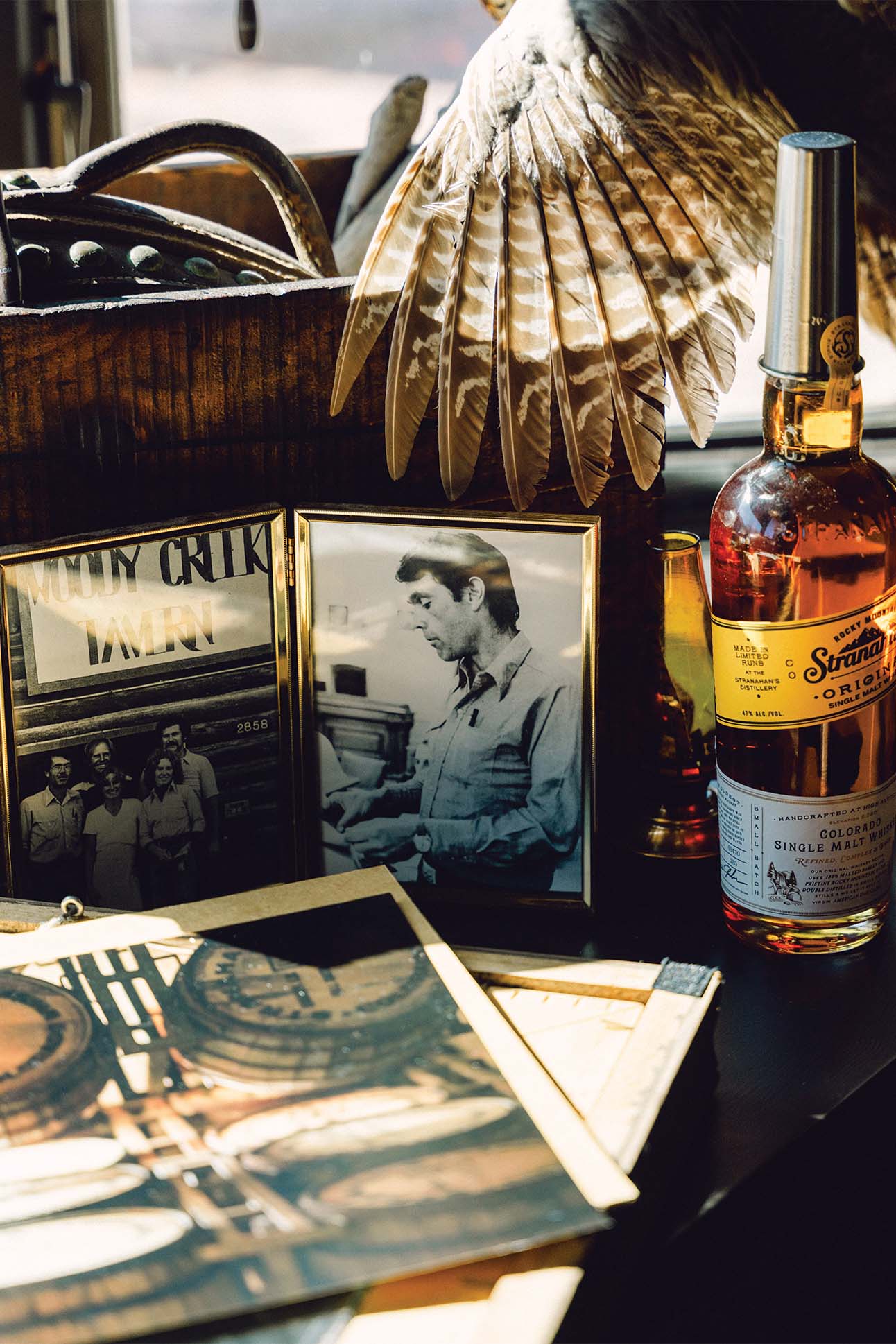

So, when Jess Graber began distilling whiskey as a hobby in Woody Creek in the 1970s, he was tapping into a long history of booze experimentation. What the contractor initially made would probably qualify more as moonshine than a true spirit, but he read and practiced, and friends seemed to like the end product. “I would give it out as Christmas presents,” Graber recalls. “It was better than giving them cookies.”

When people started requesting bottles, Graber realized his hobby had the potential to turn into a real business. Then fate intervened: In 1998, Graber, a volunteer firefighter, was called out to George Stranahan’s property about three miles away for a barn fire. After helping extinguish it, Graber got to talking with the founder of the Flying Dog Brewpub. He asked if he could use one of the still-standing barns for distilling. Stranahan agreed.

They didn’t know it yet, but this was the beginning of a beautiful whiskey story.

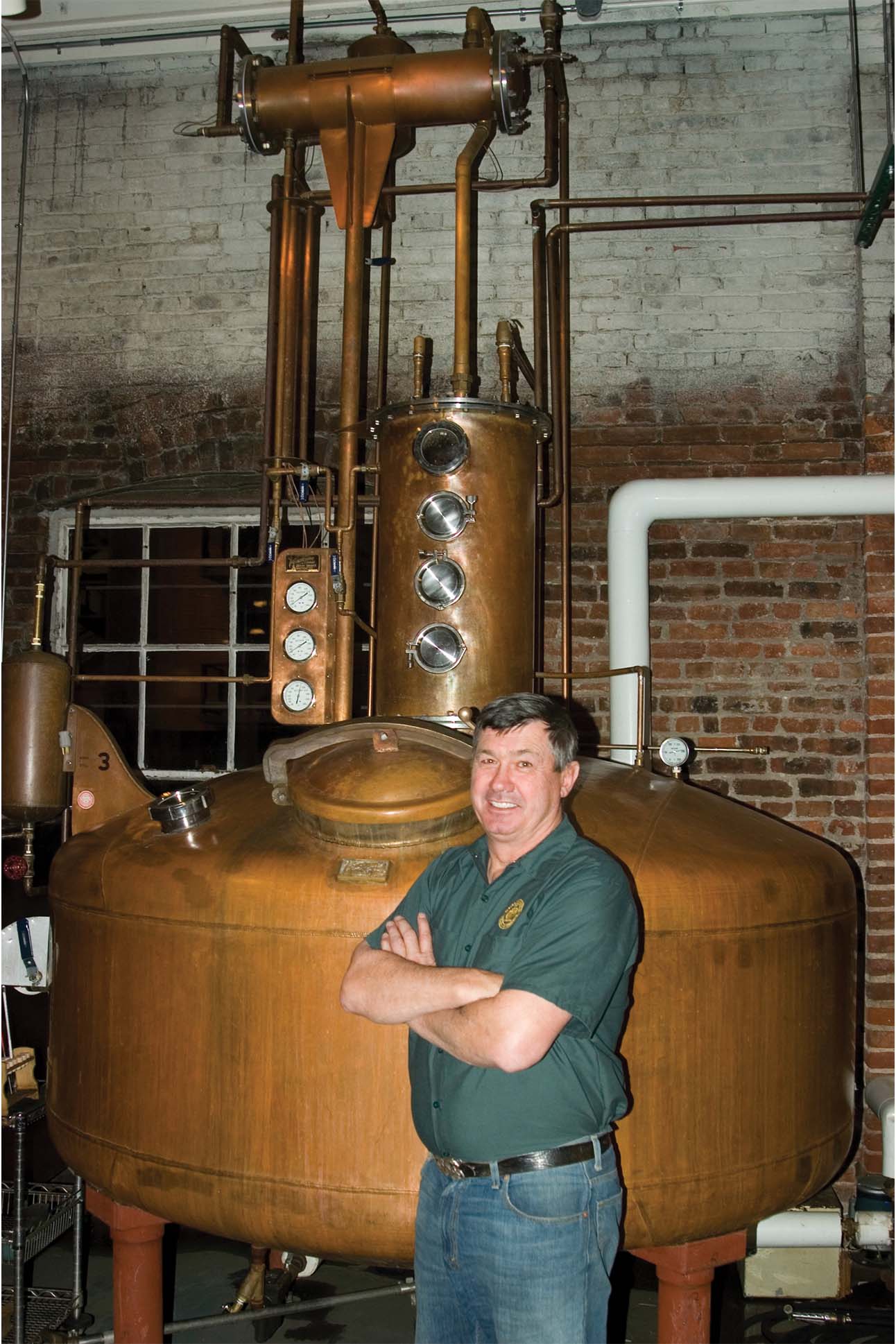

A year or so later, Graber had a eureka moment. While working in Stranahan’s barns, he used some leftover kegs during the distillation phase, creating a beer mash. It was something no other distiller was doing at the time, and when Graber filtered the resulting liquid, he discovered that he could create a purer, smoother, more flavorful product. He kept experimenting until he had a recipe that was solid: a single malt whiskey made in small batches from malted barley, yeast, and Rocky Mountain water.

He approached Stranahan with a proposition to open a distillery next door to Flying Dog (which by then had moved to Denver). The brewer wasn’t convinced, but Graber had an ace up his sleeve: The new distillery would be called Stranahan’s.

And so, just a few years later, Stranahan’s was founded, becoming Colorado’s first licensed distillery since Prohibition. It was a bittersweet accomplishment—and an homage of sorts—as George Stranahan passed away in May 2001. It surely would have made its namesake proud: The Denver distillery has amassed a massive fan base and numerous awards, including gold in the 2021 World Whiskies Awards.

And now, more than two decades after its founding, Stranahan’s has finally returned to the Roaring Fork Valley with Stranahan’s Whiskey Lodge. “George Stranahan was a legend—we all grew up knowing who he was,” says the lodge’s general manager Max Ben-Hamoo, a born and raised Aspenite. (His father, Shlomo, once operated an eponymous deli at the base of Aspen Mountain and, later, in restaurant spaces at The Little Nell and the Residences at The Little Nell.) With the Whiskey Lodge, Stranahan’s “really wanted to go back to their roots,” Ben-Hamoo says.

Guests at the downtown venue step into a dark wood saloon, with pickaxes hanging above the door, to taste Colorado’s whiskey in drams, flights, or classic and seasonal cocktails. A few offerings are even unique to this mountain location, including the Alexander Hamilton (a blend of Stranahan’s Sherry Cask finished with rosemary-fig syrup, lemon, and mint) and the Rita Likes Whiskey (a spicy whiskey margarita).

“Whiskey has for a long time been pigeonholed into you drink it either on the rocks or neat or maybe with a little bit of water,” Ben-Hamoo says. “We take that on as a challenge. What are all the different ways that we can express whiskey in a cocktail?”

Food is similarly creative. The elevated pub bites not only complement the available spirits, but the ingredients are often cooked with them, too. Chef Nick Ragazzo makes a whiskey-smoked Colorado Wagyu brisket and single malt mustard for the pretzel hot pocket. There’s also rigatoni alla whiskey and apple-butter dipping sauce—made with the Aspen Exclusive whiskey—to accompany the apple cider beignets.

The lodge also presents an opportunity to try Stranahan’s American single malt, a unique offering that was so unheard of in its early days that the company referred to it as Colorado whiskey to help explain why it tasted different from others on the market. In December, the government officially—finally—recognized the American single malt whiskey as its own category. In order to qualify, the spirit must, among other things, be made in the United States from 100 percent malted barley and matured in oak casks. Stranahan’s is aged for a minimum of four years.

“Stranahan’s blazed a trail in the category of American single malt; it blazed a trail in craft distilling period,” says Justin Aden, the distillery’s current head blender. “It’s a style of American whiskey that’s a little different than anything else. We set out to make a reflection of what our people in Colorado know how to do and reflect our place.”

Aden sees their product as a reflection of Colorado itself too: “We can grow and malt barley here really well—it was only a matter of time until a maverick, a pioneer came along and said, ‘Let’s make whiskey out of it.’”

Stranahan’s American single malt recipe is the same one Graber perfected all those years ago. Volunteers still help bottle the whiskey multiple times a month alongside Stranahan’s staff. The experience is so popular that the distillery randomly draws names for each shift from a waitlist of around 25,000 people. The tin caps on top of the bottles—a nod to what Colorado miners once drank from—and sloped labels haven’t changed much over the years either.

But that’s not to say that Stranahan’s hasn’t evolved.

By taking its base spirit and finishing it in barrels from around the globe, Stranahan’s has developed a variety of different expressions. The most recent Diamond Peak release was aged in Caribbean rum casks, for example, and the Aspen Exclusive—which, as the name suggests, is only available in the mountain town—was aged in Calvados French apple brandy casks. (A portion of the sales of Aspen Exclusive bottles benefits the Aspen Fire Protection District in honor of Graber.)

And every December, hundreds of people line up outside the Denver distillery hoping to get one of the limited-edition Snowflake releases that blends a variety of finishes into a single bottle. It sells out within hours.

“The creativity behind it is what the spirit of Stranahan’s is all about,” says Graber, now 74. “It wasn’t supposed to be your grandpa’s bourbon. It was supposed to be something from Colorado. It’s a rugged state, and a cool state.” All it needed was a really great whiskey.