Text by Cindy Hirschfeld

Images by Christopher Crawford, Lia Halloran, Thomas O’Brien, and Eli Stoken

Barton Tofany recalls camping out as a child in his family’s Old Snowmass backyard and watching meteor showers and other celestial events. “When I was 5 or 6, one of the big comets was coming by, and I remember going outside to look at it and thinking it was super cool,” he says. Those experiences resulted in a lifelong love of astronomy that the Aspen High School science teacher now shares with students.

But Tofany also appreciates what he didn’t comprehend as a kid: the Roaring Fork Valley is a superb place to view stars, planets, and other objects in space. “Being born here, I thought this was always the way it is,” he admits. “It wasn’t until I got older and realized that there’s so much light pollution in other areas that you couldn’t do good stargazing there.”

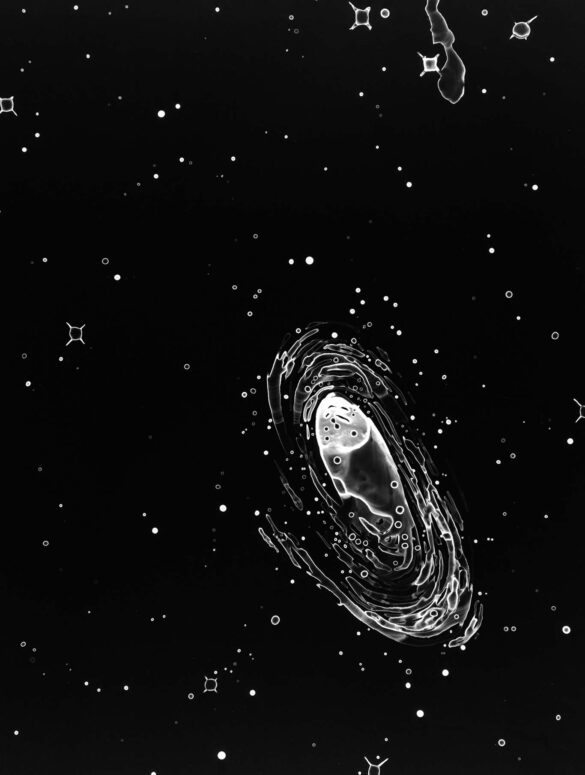

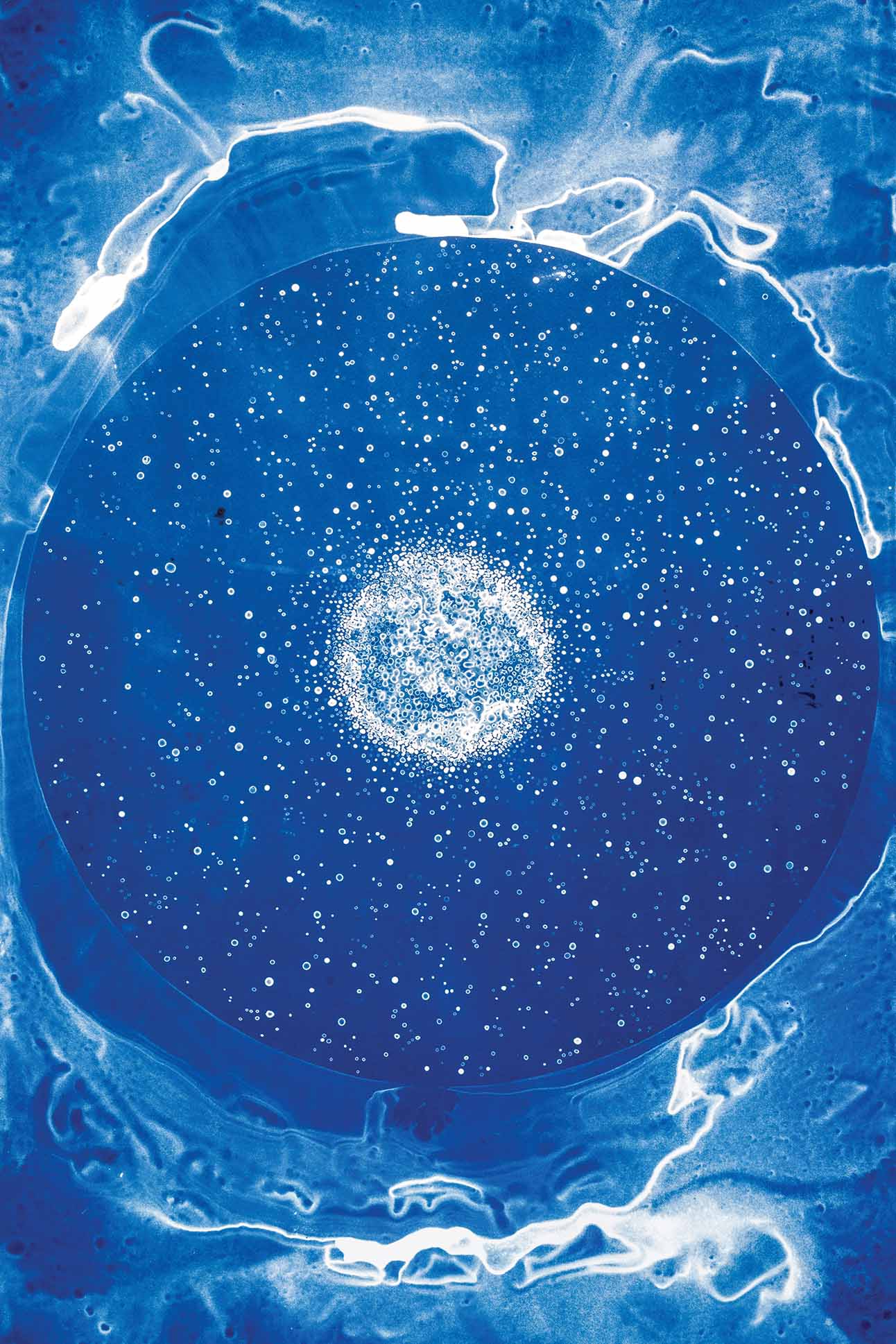

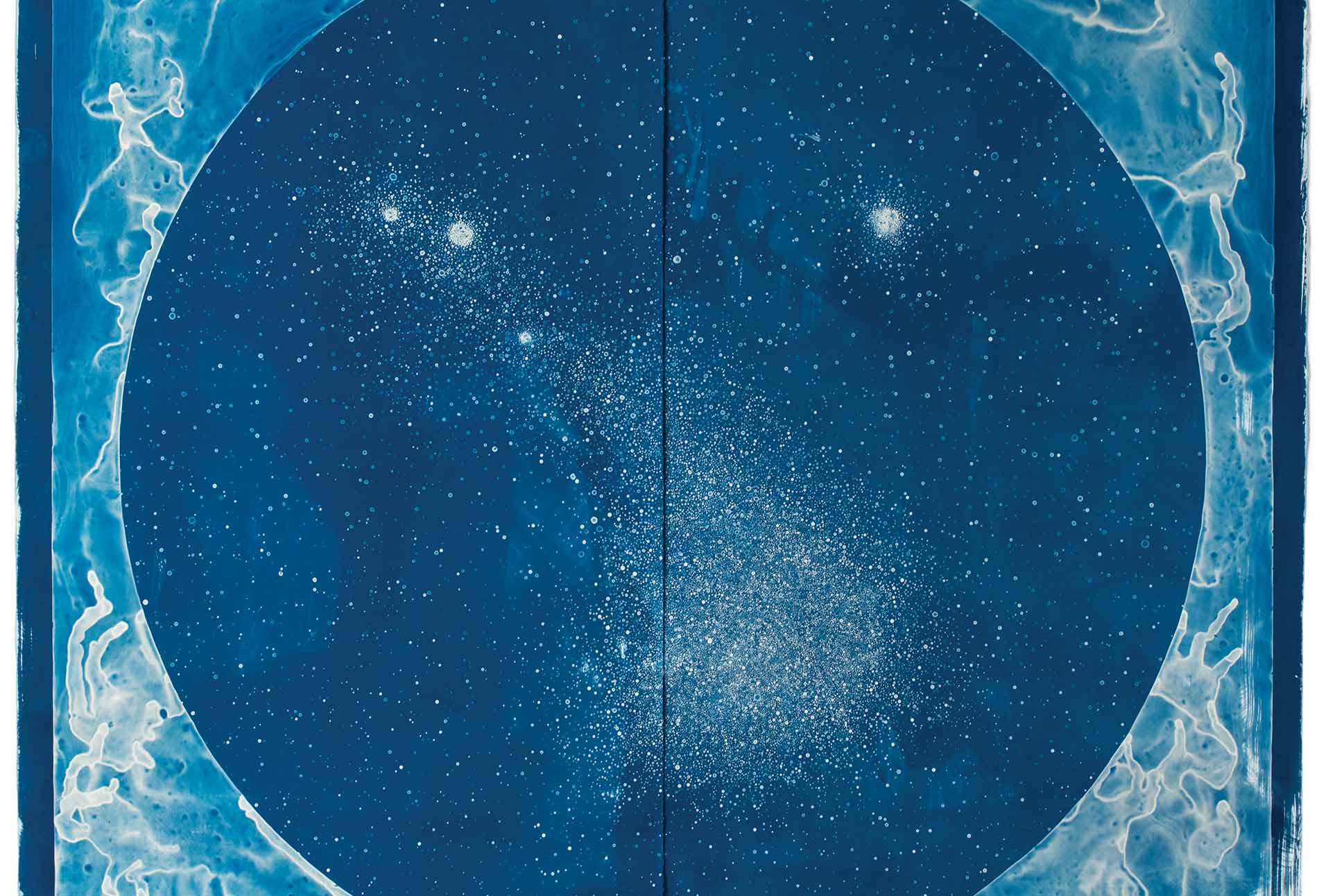

Indeed, looking up into the night sky around Aspen can astonish those unaccustomed to seeing so many stars, and with such clarity. Year-round constellations like Ursa Major, which includes the Big Dipper, and Cassiopeia, shaped like a “W,” twinkle brightly. The Milky Way often looks as if a celestial artist brushed a swath of glitter and white powder across an inky canvas.

Ryan Eliason, who runs private viewing tours in summer through his company, Aspen Stargazing, loves sharing Aspen’s advantageous setting with others. “A lot of our guests come from big cities where they can’t see a star with the naked eye, much less the details of another galaxy,” he says.

Aside from the lack of light pollution, what else makes the area so great for seeing stars? The atmosphere holds less humidity at high elevation, which makes the view of space clearer. Plus, Eliason says, “Our weather is pretty amazing, with more than 300 clear nights a year.”

On top of all that, it turns out that winter, especially, is not only great for carving turns down Aspen Mountain but also for spotting what’s in the sky. Cooler temps translate into even less humidity, which Eliason says makes the sky look “a little bit crisper.”

Some constellations only appear at this time of year. “The winter night sky is a fun one,” Tofany says. Orion, the hunter, stalks through space, easily recognizable by his three-star belt. (“You’ll always see it if you’re facing south,” Tofany notes.) Nearby, Canis Major, the Great Dog, includes Sirius, the sky’s brightest star. Taurus (which encompasses the star cluster Pleiades, also known as the Seven Sisters) and Gemini, as well as planets such as Jupiter, Saturn, and Venus, also light up the night.

In addition, the winter brings a trio of meteor showers: the Geminids, which peak in mid-December, followed by the Ursids in the second half of the month and the Quadrantids in early January. And in late January, Venus, Mercury, and Mars will align in the morning sky before sunrise—among the few planetary alignments that occur throughout the year, Eliason says.

To see all the celestial action, stargazers needn’t venture far from Aspen. Eliason’s go-to viewing spots include nearby Mollie Gibson Park at the base of Smuggler Mountain and Wagner Park downtown. For darker skies, he and Tofany suggest driving away from town toward the closure gate on Independence Pass or partway up Castle Creek Road. Intrepid viewers can even skin or snowshoe on one of the four ski areas. (Just keep an eye out for grooming machines.)

Beyond a feast for the eyes, stargazing also offers a poignant reminder of our place in the cosmos. “It proves the point that nothing is as big of a deal as it seems,” Eliason says. “We’re just a little blip in the grand scheme of a universe. I like that perspective.”

The Aspen Stargazer’s Guide to the Galaxy

Use an app or map to ID stars and planets.

Eliason likes the app Night Sky, while Tofany uses Stellarium Mobile. Eliason also recommends skymaps.com, which offers a different downloadable map each month.

Stargazing is best around the new moon.

Eliason won’t even run his tours if the moon has more than 70 percent illumination; otherwise, he says, “Even with a telescope, you’ll see little blobs with no details, and you won’t be able to see many stars with the naked eye.”

The sky doesn’t have to be pitch black.

Eliason says that about an hour after sunset is typically dark enough to see most details in the night sky.

Give your eyes time to adjust.

It takes at least five minutes to kickstart your night vision, which will continue to improve over the course of an hour or more, Tofany says. Averting your vision helps, too. “When you look slightly off from what you’re trying to focus on,” Eliason says, “you see more detail.”

If you can’t access a telescope, bring binoculars.

They help magnify the night sky enough that you might see the rings on Saturn, some of Jupiter’s numerous moons, or a double star in the Big Dipper, Eliason says.

Use your imagination.

“People think that constellations are going to look identical to what they’re supposed to be,” Eliason says. But it takes more than just connecting the dots to see the bull in Taurus, say, or the dog in Canis Major.